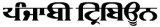

The Commissioner for Lost Causes by Arun Shourie. Penguin Random House. Pages 616. Rs 999

Book Title: The Commissioner for Lost Causes

Author: Arun Shourie

Purushottam Agrawal

YOU can idolise him as ‘the angry crusader’ or deride him as a ‘paratrooper’ and of ‘lesser breed’, but you can certainly not ignore ‘the commissioner for lost causes’, as Ramnath Goenka admiringly named Arun Shourie. He has proved to be the real ‘game-changer’ of Indian journalism, by redrawing the lines of demarcation between an activist (that too with very clear political preferences) and a journalist.

In the book under review, he revisits his most important journalistic (and, of course, political) feats with some relish and some reflection. Starting from the mid-Seventies to the end of last century, which contributed to the present state of Indian polity and society, the reader sees those important episodes through the author’s gaze.

Written in Shourie’s signature style (systematic presentation of facts and arguments in lucid prose), the volume works as a necessary reminder of important things in this era of constructed, collective amnesia.

Shourie reconstructs the most important episodes of his career here — exposure of the Bhagalpur blindings; selling of tribal women on Madhya Pradesh-Rajasthan border; fund collection scandal at the trusts set up by AR Antulay, the then CM of Maharashtra; Anti-Defamation Bill aimed at curbing press freedom; misuse of institutions, including judiciary; and distrust between the then PM Rajiv Gandhi and President Zail Singh, who even contemplated dismissing the PM and was assured of support from Ramnath Goenka and Vijaya Raje Scindia. Fortunately, better sense prevailed, the author informs us, due to his own and LK Advani’s timely intervention.

The most interesting and educative is the reconstruction of the Bofors issue, which catapulted VP Singh to the top job, but, with Devi Lal as a thorn in the flesh. Shourie does not hide his contempt for either. That there was no love lost between Devi Lal and Shourie is well known, but here we find VP Singh as a man ‘without backbone’, ‘coward, opportunist and believing in nothing’.

The chapter titled ‘A Conman Takes Us for a Ride’, makes for a hilarious and, at the same time, troublesome reading. The numbers projected by the ‘conman’ (Chandraswami) as Swiss bank account numbers turned out to be the phone numbers of Bofors boss Ardbo. This information had enthused VP Singh so much that he claimed to be in possession of “the details of the account in which the Bofors money has been deposited”.

Such enthusiasm also raises some serious questions which the author does not address. Undoubtedly, for a dedicated and enthusiastic journalist, no source (including the conman) is untouchable, but was this dedication really to the duty of exposing corruption or to bring down the Rajiv Gandhi government at all costs? Were the warriors against corruption enthused by genuine consideration for probity or by politics of a certain kind?

Summarising ‘some of the lessons’ at the end, Shourie writes: “Our task is to educate people… not to merely entertain... to provide diversions.” One couldn’t agree more when one sees professional comedians faring better than many ‘journalists’ in the ‘task to educate people’. But the unaddressed question remains: where does the ‘educating’ end and instructing in favour of a certain political line begin?

This book is not a nostalgic tour down memory lane, but an attempt to look back and recall the past in order to assess the present and imagine the future. Shourie makes it clear at the outset: “We exposed corruption. It is hundreds and hundreds of times larger today… We railed against the misuse of an institution. Today, all institutions are instruments, and are accepted as such. We nailed the lies of a Minister, of a Prime Minister. Today, that the ruler has heaped yet another truckload of falsehoods on our heads is just what we expect… But the fact what is happening today was also happening then is no excuse... That does not explain away organised slaughter, it does not explain away either serial ‘encounters’, or sanctioned and sponsored lynchings. I, therefore, sincerely hope that incidents set out here will not fuel ‘Whataboutery’. ‘Kam-bhakts’ (the worshipper-pests) tempted to put this volume to use that way would find it prudent to wait for the next one!”