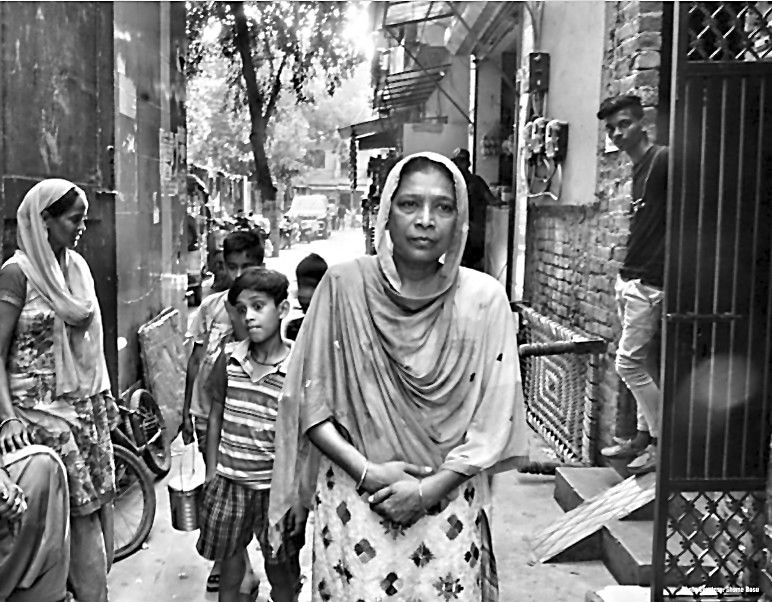

‘The Kaurs of 1984’ by Sanam Sutirath Wazir: 40 years on, retelling the horrors

Ajaz Ashraf

‘I was raped collectively — by the entire Congress government. All of them, including the Prime Minister, President, Home Minister and, in fact, everyone in this country who failed to protect us,” Satwant Kaur told Sanam Sutirath Wazir, the author of ‘The Kaurs of 1984’. Satwant was recalling the hours following the assassination of Indira Gandhi on October 31, 1984, by her two Sikh bodyguards, when mobs of Hindus descended upon Delhi’s Sultanpuri Colony, where she lived. They killed men wearing the turban, set houses on fire, and leisurely took to brutalising women.

by Sanam Sutirath Wazir.

HarperCollins.

Pages 256. Rs 399

Satwant was whisked away to a place where four men took turns to rape her, egged on by the women of the household. She heard an old woman say, “Don’t leave these whores. They killed our mother.” There were others who were brought there and raped. Naked, Satwant walked home, groped by men and laughed at by women. Satwant still lives, 40 years later, struggling to ward off the past from intruding upon her present.

Satwant’s story constitutes one of the many fragments of national memory forgotten or suppressed or ignored — and now retold, and relived, in ‘The Kaurs of 1984’. There was a ‘before’ to the fury into which Satwant was sucked. The before could cover a decade of complicated political processes, through which the demand for greater autonomy for Punjab triggered a militant movement for carving out an independent state, Khalistan.

But the before in ‘The Kaurs’ begins in June 1984, when Operation Blue Star was conducted to flush out militants, led by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, from the Golden Temple complex. The damage to the complex was extensive. The violation of their sacred space traumatised a large segment of Sikhs, whose alienation further deepened over the violence the Indian State allowed to be perpetrated against the community outside Punjab after the assassination of Indira Gandhi. Militant bands mushroomed and invited, not unexpectedly, a brutal police crackdown.

Wazir does not tell the story of Punjab’s slide into abyss, which only provides a backdrop to the torrid times through which the women in Wazir’s book lived, and whom he tracked over some years. They narrate their stories to him. And he threads them together, at times disjointedly, into a pastiche of memories. It becomes an alternative to the histories men have written on the before and the after of the 1984 pogrom, as experienced and narrated by Sikh women.

Horror is the leitmotif of the book. This is most tellingly narrated in the voice of Darshan Kaur, a resident of Block 32 of Trilokpuri Colony, Delhi. After most men of her neighbourhood had been killed, the women were assembled in a park, and gangs of men ferreted away the girls they fancied. Later, she saw Congress leader HKL Bhagat step out of his “gleaming white ambassador”, dressed in a “white kurta-pyjama”, receive a rapturous welcome by Trilokpuri’s butchers and rapists. White contrasted with the colour of blood!

Darshan is not like many other women in ‘The Kaurs’, a passive, inert being. Years later, in a Delhi court, she took off her slipper, pointed it at Bhagat and identified him as the leader who “urged the mobs to kill the Sikhs”. But not all took recourse to court to seek justice. A young Nirpreet Kaur saw her father being burnt alive by the “goons of Sajjan Kumar”, then an upcoming politician, whom the Congress subsequently fielded in the 1984 Lok Sabha elections. He won. It shattered Nirpreet’s faith in the system. She joined the Sikh militant movement and insisted she be married to a gun-toting man before undertaking a mission in Delhi — but was arrested. Nirpreet’s recompense was, ironically, the court, where she testified against Kumar, now in jail.

Not all women joined the movement to avenge the killing of their relatives — some did because their sentiments were roiled by Operation Blue Star. Others did because they were as affected as men were by the zeitgeist, the spirit of the Punjab of the 1970s and 1980s. Of such women too, the book tells the stories, in their voices. These, too, can make you recoil in horror.

For instance, a woman speaks of how she enticed a communist activist to walk into the trap laid by militants. The activist’s head was later found at the entrance to the village. Another woman narrates her experiences of crossing into Pakistan multiple times, to secure assistance for the cause of Khalistan. And then there are horrific tales of the police beating up women mercilessly, giving them electric shocks and, in one instance, raping her. Most of them were not militants. They were tortured in order to have them divulge the whereabouts of their relatives.

‘The Kaurs’ does not tell, in any detail, the horror the militants themselves perpetrated against both the Sikhs and Hindus, killing them at random or for having the temerity to speak out against them. This, in a way, leaves Wazir’s story incomplete. But it can also be argued that he never set out to provide an authoritative account of the experiences of women who lived through Punjab’s torrid years. The brief he lays out for himself is to show how the State can, through its inaction and action, brutalise its own citizens, and that it cannot become partisan in ethnic conflicts. It will, otherwise, produce the Satwants, who will say the government raped them — as many Muslim women, too, must have thought during the 2002 Gujarat riots.

The tales of horror recounted in ‘The Kaurs’ will likely perturb many into wondering about the need to spotlight the wounds inflicted on citizens in the past. But the wounds the women suffered continue to bleed and hurt. They will not heal until they see the light of justice and their lives, wrecked in 1984, acquire a semblance of normalcy. ‘The Kaurs’, in the 40th year of the 1984 pogrom, is a reminder of what the State ought not to do.