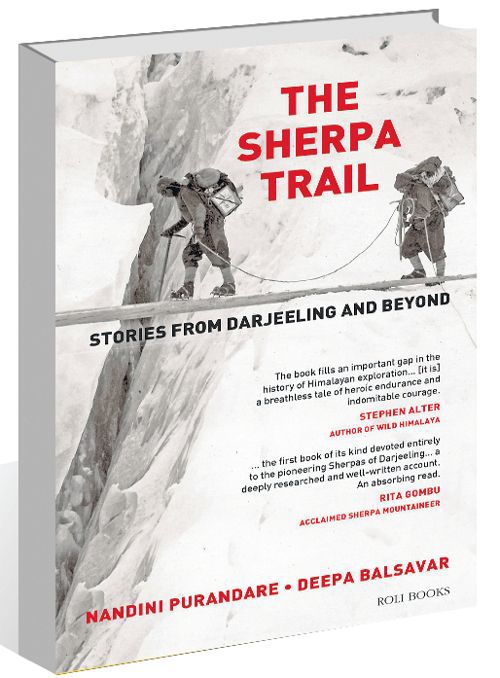

‘On Sherpa Trail’ by Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsava is a long overdue tribute to the Sherpas

Avay Shukla

This book is a well-deserved tribute to perhaps the most recognisable group in the community of mountain climbers, but about whom next to nothing is known apart from their climbing exploits. The Sherpas are almost synonymous with the Himalayas and the 8000ers and their histories cannot be separated.

This wonderful book, based on visits, interviews and documented records, finally does justice to this most intrepid, strong, courageous and loyal of our species.

The Sherpas (like the Bhutias) were originally residents of eastern Tibet and migrated to Nepal hundreds of years ago. Subsequently, in the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a second migration to Darjeeling in India, once a part of Sikkim, but annexed by the British in 1850. For, Darjeeling was a two-way gateway: north to Nepal and Tibet for expeditions to the Himalayas and south for trade and other employment.

The age of climbing in the Himalayas began in the last two decades of the 19th century, as an extension of European and British imperialism, and that is when the Sherpa came into his own. Nepal was closed to foreigners till 1949 and so initially all attempts on the Himalayan peaks were through Darjeeling and Tibet. It soon became clear that the Alpine style of climbing and European supporting staff were unsuited for these altitudes and conditions, and so hundreds of native Lepchas, Bhutias and Sherpas were hired as porters and guides for these expeditions. A new profession was born and the Sherpas dominated it.

The book is a fascinating account of the history of mountaineering in the Himalayas; the various expeditions to different peaks like Everest, K2, Kanchenjunga, Nanda Devi, Dhaulagiri, Nanga Parbat; the conquests, failures and tragedies that resulted; the famous climbers associated with them and the role played by the Sherpas in these attempts. It traces the evolution of the Sherpas from unnamed individual porters to their recognition as mountaineers par excellence, sealed by the achievement of Tenzing Norgay on Everest on May 29, 1953. The Sherpas now acquired names, faces, respect and fame.

The book traces the establishment of THC (The Himalayan Club) in 1929 (out of its 250 members, only one Indian, the Raja of Jubbal in HP, found a place in it!) to coordinate all climbing expeditions in the Himalayas and to extend the knowledge of the Himalayan ranges for the benefit of science, literature, art and sport. It also acted as a bridge between the Sherpas and the expeditions. We learn of two British ladies — Joan Townend and Jill Henderson — who as honorary secretaries of the THC contributed a lot to the recognition of the Sherpas as more than mere porters and did much for their welfare. Sadly, as much of the mountaineering (and Sherpas) shifted to Nepal after 1949, the THC’s role began to diminish. The process was speeded up by the setting up of the HMI (Himalayan Mountaineering Institute) by Nehru at Darjeeling in 1954, the Sherpa Climber’s Association by Tenzing in 1955 and the Indian Mountaineering Federation in 1961. But it had done its job well by then.

There are chapters on some of the legendary Sherpas such as Pasang Dawa, Ang Tharkay (probably the greatest of them all), Khamsang Wangdi, Nawang Gombu (the first person to have climbed Everest twice), Dorjee Lhatoo (the Clint Eastwood of Darjeeling!), Pemba Chorty (he has summited Everest an incredible seven times), and Ang Tsering (who is reported to have discovered the footprint of a Yeti and received a hundred rupee bonus for it!), whose achievements matched that of Tenzing Norgay even as all the glory went to the latter.

There is a full chapter on the Sherpanis, Ani Lhakpa Diki (“the most gorgeous woman in all of Darjeeling”) and Ani Daku Sherpa, to remind the reader that the women of the tribe matched their male counterparts, step for step, load for load, at least till base camp. These thumbnail vignettes bring the reader into the homes of these doughty heroes, to give us a glimpse of their past, present and future. Theirs was a hard life: almost all of them were migrants from Tibet or Nepal. Childhoods spent in poverty, they raised themselves to unprecedented heights, by dint of sheer hard labour and commitment, and then reverted to humble retirement. They were legends in the climbing world, but are almost unknown outside of it. One achievement of this book is to have made them known to the larger world.

The authors also do their best to profile Tenzing himself, to contrast the pre-Everest and post-Everest hero. Where the former was an amiable, fun-loving, helpful individual, the later Tenzing comes across as one full of grievances, petty jealousies and even vindictive. All the adulation, success and riches appear to have gone to his head; he even turned against his former friend Ang Tharkay and had him evicted from HMI. In fact, Capt MS Kohli, a member of the Indian Everest Expedition in 1962, went so far as to tell the authors in 2014: “As a human being, Ang Tharkay was a step further than Tenzing.” Some feel that he became “a slave to his greatness” but in extenuation, it must be said that it could not have been easy for him, an uneducated man from a humble background, to have faced his global celebrity status and the pressures, demands and expectations that came with it. Though not a Sherpa himself, he made the Sherpa a household name. That, along with Everest, will remain his lasting legacy.

The book ends on a somewhat sombre and despondent note: that the golden age of the Darjeeling climbing Sherpa is now almost over. In fact, it quotes one great mountaineer as saying that in a decade from now, there will be no Sherpas on the mountains. There are reasons for this: major expeditions to Everest have shifted to Nepal and the younger Darjeeling Sherpas have followed suit; the present generation of younger Sherpas is not interested in doing what their fathers did. They are educated, ambitious and do not see either climbing or high-altitude portering as a viable future; the HMI in Darjeeling has lost much of its lustre to the IMF (Indian Mountaineering Federation), its original Sherpas elbowed out by bureaucrats and Army personnel, both as administrators and instructors.

The elegy for this unique breed of mountaineers is perhaps best provided by Nima Norbu, an Everester himself and the brother of Tenzing Norgay’s third wife. This is what he told the authors: “Ninety nine per cent of the educated Darjeeling Sherpas are not going into mountaineering… There is no future for the climbing Sherpas of Darjeeling. When HMI opened, that was a different time. The whole system has changed. There are very few Sherpa instructors in HMI, and none in other institutes like at Uttarkashi and Manali.”

This book ensures that when the Sherpa goes, he will not go unsung or be forgotten.