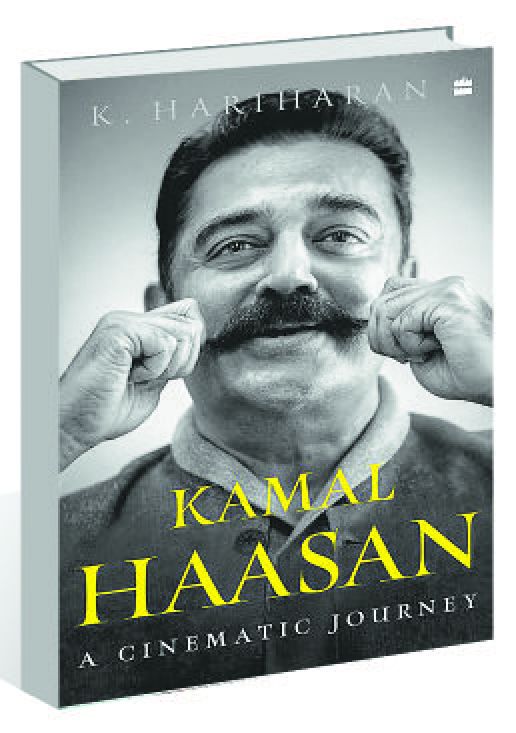

‘Kamal Haasan: A cinematic journey’ by K Hariharan: A phenomenal actor’s cinematic odyssey

Nonika Singh

Kamal Haasan’s latest offering, ‘Hindustani 2’, may have disappointed critics and audiences alike, but who can dispute the superstar filmmaker’s commanding position in Indian cinema. Surmising an actor of over 260 films in 250-odd pages is an onerous task, yet K Hariharan, himself a National Award-winning filmmaker, rises to the challenge with an exceptional understanding of both the actor and his cinema.

Almost each chapter of K Hariharan’s book on Kamal Haasan is an in-depth study, a revelation of his art

Almost each chapter of the book is an in-depth study, a revelation, as he succeeds in taking us through a fascinating cinematic journey. With his word wizardry, Kamal Haasan’s cinema and what it stands for come alive lucidly and in enriching ways.

in ‘Kalathur Kannamma’ (1960).

Let it be said at the very onset that this is not a standard biography. It, of course, starts with the actor’s birth. In a dramatic tone, with a dramatic flourish, we are told how his mother miraculously survived a difficult childbirth and three-day-old Kamal Haasan began to respond to his surroundings. His sister calls his birth divine intervention, but also states how her younger brother does not believe in god. We are also made privy to his naughty antics as a child, which landed him his first film at the age of five. These, however, are just a few personal details that dot the book. Hereafter, the actor and his cinema take centre-stage and we see the living legend primarily through the lens of his movies.

As the ‘reluctant’ actor emerges, there are no regular epithets to edify or embellish his immense acting prowess. Adjectives do not come from a fan boy diary but from a keen observer, an astute cinephile.

The vast range of the actor pulsates not merely through a host of movies, but significantly through the author’s deep insight and reflections. Kamal Haasan, whom we have seen carry a silent movie (‘Pushpak’) on his shoulders, turn into a dwarf (‘Apoorva ‘Sagodharargal’), become a woman (‘Chachi 420’), play a blind violinist (‘Raja Paarvai’) and start his career with an unconventional part of a villain (‘Arangetram’), is clearly not just another actor in the firmament. Yet, for someone who went on to do over 150 films between 1972 and 1987 alone, he believes he has ‘achieved just 25 per cent’ of what he set out to do.

His film trajectory is not a by-the-numbers account, but unfolds through vivid imagery and incisive commentary. The pattern — a brief outline of the films, character study, followed by the author’s perspective as well as its fate at the box-office — might sound a bit repetitive. But if movies like ‘Ek Duje Ke Liye’ have entranced you, so does Hariharan’s exposition of their myriad dimensions. Talking of ‘Ek Duje’, which turned out to be a massive pan-India hit, an interesting bit of information is that to begin with, there were no takers for the Hindi film. Equally engrossing is the fact that for his part as a dwarf in ‘Apoorva Sagodharargal’, a pit was dug as those were not the days of computer-generated imagery (CGI).

The cinematic diegesis, subtexts, the underlying meanings and often what the makers did not perhaps even intend to allude to are seen through Hariharan’s perceptive eye. He places Haasan’s films in the unique feminist discourse, socio-political milieu and reminds how like German filmmaker RW Fassbinder, K Balachander, the director with whom Haasan acted in no less than 26 films, too, was ‘struggling with the dilemma of Tamil identity politics’.

Since no art exists in isolation, how can the cinema of ‘new folk tale narrator’ Balachander? His work “addressed the ‘form’ of a failing system, the so-called orderliness which has failed to support the growing problems of modernity and democratic aspirations”. In this book on Tamil cinema, while names like Sivaji Ganesan, Rajinikanth and Sridevi are a given, surprisingly, references to political figures, especially Indira Gandhi and Jayalalithaa, too, are contextualised.

The who’s who of the world of cinema, who impacted or inspired some of Haasan’s movies, find mention. Hariharan also factors in audiences’ reactions. Why they lapped up a few films like ‘Vikram 2’ and why they possibly rejected some complex ones such as ‘Aalavandhan’ and ‘Uttama Villain’ (written and produced by Haasan too) is elucidated with credible reasoning.

He refers to Slavoj Zizek’s concept of ‘surplus enjoyment’ to explain the ‘global appeal of shocking, disturbing and excessive content’.

Kamal Haasan, we are reminded, often says, “I want to be the best rasika, the best fan cinema could ever have.” His cinematic odyssey sure has been recorded by a true savant.