Hastings in Haryana: British Governor-General’s insightful journal on his trip from Bengal to Punjab

Subhash Parihar

Many British administrators maintained journals in which they kept a record of their own activities, and significant events of their life and times. One such journal was kept by Francis Edward Rawdon-Hastings (1754-1826), the Governor-General between October 4, 1813, and January 9, 1823. The East India Company at that time directly controlled only the Madras, Bengal, and Bombay presidencies.

During his tenure, Hastings supervised the British victory in the war against the Gurkhas of Nepal (1814-1816), the final British conquest of the Marathas in 1818, and the purchase of the island of Singapore in 1819. He also brought many Indian states into subsidiary alliance, besides carrying out educational and administrative reforms.

To inspect the British possessions in India, and to meet Indian rulers and notables, Lord Hastings undertook a long journey, from his headquarters in Bengal up to southern Punjab (now Haryana), and back. He began his voyage in June 1814 from Barrackpore, and completed it in 17 months. He died in 1826. About three decades later, his daughter Lady Sophia published the journal.

Lord Hastings hired the services of a major Indian artist, Sita Ram. His paintings are preserved in eight albums (originally 10), now acquired by the British Library, London. Recently, JP Losty, the former curator-in-charge of the Indian visual collections in the British Library, re-published the journal in the form of a beautiful book, ‘Picturesque Views of India, Sita Ram: Lord Hastings’s Journey from Calcutta to the Punjab, 1814-15’ (Roli Books).

Hastings passed through Murshidabad, Patna, Benaras, Allahabad, Kanpur, Lucknow, Moradabad, Hardwar, Karnal and Hansi. His return journey up to Kanpur was by a slightly different route, via Mathura, Agra and Farrukhabad.

The retinue crossed the Jamuna from the Saharanpur side on January 2, 1815, and passed through Kunjpura, Karnal, Jind, Hansi, Bahadurgarh and Narela. On January 27, he re-crossed the Jamuna at Baghpat. On the method adopted to cross the river, he wrote: “Though this may perhaps be reckoned its lowest period, it is a great body of water. I forded it on my elephant. The bottom is sand. It is firm where I passed, but in other parts three or four elephants were much embarrassed by sinking in it. While the elephant is thus entangled, they give large fascines of brushwood, and he will with his trunk place them under his leg, so as to enable himself to draw up his feet out of the quicksand. Some camels had stuck fast near the western shore. Ropes were tied around them with the ends fastened to elephants, which readily dragged the camels out of their difficulty.”

On the way to Karnal, Nawab Rahmat Khan, ruler of the small state of Kunjpura, met Hastings. The Nawab was aware that the British cantonment of Karnal, between his state and the Sikh chiefs, rendered him safe from the Sikhs. Hastings noted that the inner and outer walls of the ditch of Kunjpura, made of “brick, laid pattern-wise, so as to produce a handsome effect”, were in a good condition.

On reaching Karnal, his retinue camped in front of the cantonment, the town lying at some distance in the rear. He felt that as compared to Meerut, Karnal was more suitable for stationing a body of troops as there was no great river between Karnal and Delhi on the one hand, and between Karnal and Ludhiana on the other, which swelled in rainy season, and made the passage difficult to traverse.

At Karnal, he inspected the fort and the artillery depot, which was originally a serai, erected for the convenience of travellers between Delhi and Lahore. Most probably, it was Serai Bhara Mal, built during the reign of Akbar (1596-1605).

Hastings described it as follows: “The building converted into a depot is square, with two elegant gateways. The arched accommodations all round afford excellent storage. The roof, supported by those arches, is flat and forms a broad rampart walk behind a good parapet. An excellent ditch, secured by the fire of towers at three of the corners, renders the defensive state of the depot nearly complete. The part where the work has not been perfected is the fourth corner, where the plan could not be continued without destroying a large tree, under which a fakeer had taken up his residence. Leaving an object of great public concern unfinished on this account shows the attention which is paid (and wisely) to the prejudices of the natives.”

It was General Hewitt, erstwhile commander-in-chief, who ordered appropriation of the serai. But “Lt Col Worsley, then Adjutant General, being more intimate with the feelings of the natives, lamented the impression likely to be made by this perversion of a charitable institution: therefore, he purchased a neighbouring spot of ground, and built on it, at his own expense, a serai of equal extent (though not equally ornamented)”.

In the area of Karnal, Ali Mardan Khan, a prominent Persian noble of the period of Shah Jahan (1628-58), had dug a canal from the place where the Jamuna came out of hills into the plains, up to Delhi. Hastings traced for a considerable distance the remnants of this canal. According to him, the object was to “fertilise the long tract of country from its source to its termination; in which extent no tolerable water is to be produced but by sinking wells to such an enormous depth as is beyond the compass of ordinary funds. All the water found in the higher strata is brackish and is deleterious to vegetables as well as unwholesome for man… This noble work of art formerly rendered the country through which it passed an absolute garden; and the sums paid by the several villages for the privilege of drawing water from the canal, furnished a considerable revenue to government… During the wars, which for a long period wasted the country between the Sutlej and the Jamuna, the banks of the canal were broken in many places, and its course stopped… no set of men found an interest to excite their negotiating for restoration, or perhaps saw a chance of prevailing on the Sikhs to allow it. The country has now, in consequence, an air of desolation. Ruins of villages meet the eye everywhere…”

In the middle of the day, Hastings had a durbar, attended by Maharaja Karam Singh of Patiala, along with his minister Misr Naudh Roy, Raja Bhag Singh (Jind), Bhai Lal Singh (Kaithal), Bhai Ajit Singh (Ladwa), Fateh Singh (Thanesar), and his nephew. Each of them presented Hastings a bow (without any arrow), as a symbol of surrendering their power into his hands. Hastings presented “a new fashioned English gun” to the Maharaja of Patiala. Making use of the occasion, Hastings acquainted them of his intention to repair the canal.

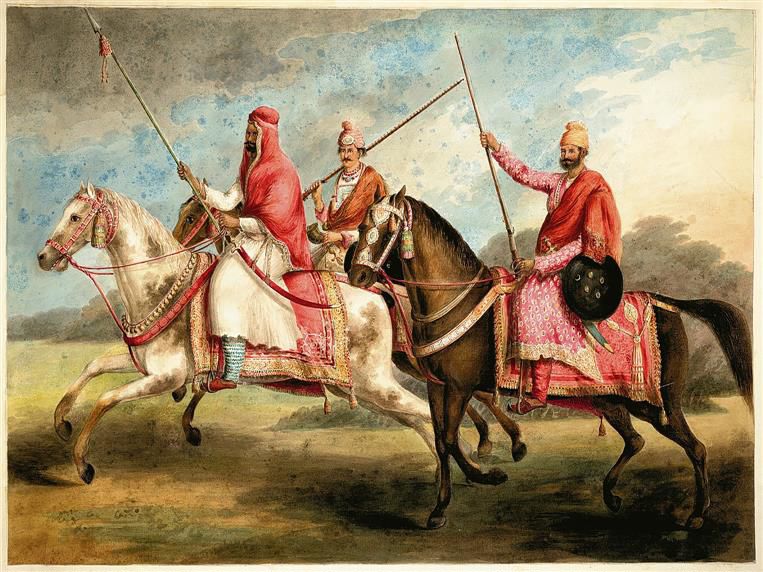

Writing about the Sikh Rajas, Hastings describes them “as a bold, athletic, and animated race”. The chiefs and attendants were richly dressed, but in a martial way. They all wore “a scarlet turban, wreathed very close and high, so as to be almost conical, which appears fashioned for activity. Their several escorts of troops were handsome and soldier-like….”

At another place, Hastings is again all praise for the Sikhs and Jats: “They are not bulky, but they are tall and energetic. Their step is firm and elastic; their countenances frank, confident, and manly; and their address has much natural politeness. I noticed the same appearance in the Rohillas and Patans (Pathans), but with less of cheerful air than I observe in the Sikhs. More active, brave, and sturdy fellows can nowhere be found than these tribes present.”

On January 10, the retinue proceeded to Jind and encamped in front of its fort. About this town, Hastings writes that it “covers a small hill, and it has at a distance a showy appearance which gradually declines as a nearer approach affords a more distinct one. The place is fortified in a manner to be respectable against a native force. The fort, or citadel, which contains the palace, is within the town, and shouldered by the houses. As it is built on the most elevated part of the hill, it looks over everything. From the manner in which the works and buildings are huddled together, it would soon be reduced by a proper proportion of mortars.”

On January 13, Hastings’ retinue reached Hansi, at that time the headquarters of Col James Skinner (1778-1841). He gives valuable information of its fort, only parts of which survive now: “The fort stands on an elevation considerable for this country; and as the hill is insulated and abrupt, it is a striking object… It was the favourite stronghold and residence of George Thomas, well known for having during a considerable time maintained an independent dominion over a large tract of territory here… as a frontier post, Hansi is very advantageously situated; therefore, it is expedient to keep up the fortress.”

On January 15, Hastings received Jaswant Singh, the Sikh chief of Nabha. On January 21, he marched to Bahadurgarh and observed that formerly it has “been a place of no mean rate, but it has much fallen into decay”. On January 26, Hastings reached Narela. Here, Begam Samru (1753-1836), the ruler of Sardhana, a small principality near Meerut, came to pay her compliments. The next day, he crossed Jamuna at Baghpat, entering what is now Uttar Pradesh.

The writer is a Faridkot-based historian