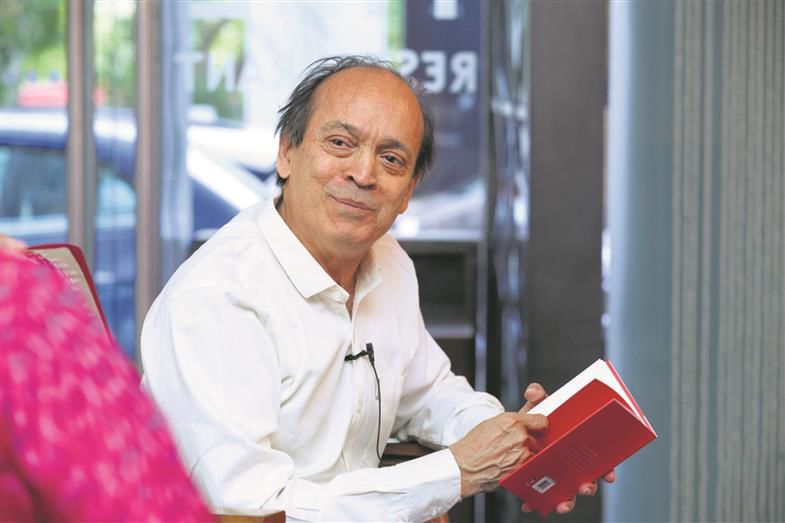

Suitable Verse: Mrinal Pande reviews and speaks to Vikram Seth about his translation of Hanuman Chalisa

In a multicultural country like India with a long colonial past, the literary arena is rife with conscious and unconscious biases. One of our most ancient sagas, Ram Katha, or the story of Ram’s life, has thrown up many versions in various Indian languages over the centuries.

Of these, 16th century saint-poet Tulsidas’ output in Awadhi proves how at various points in time, the line dividing aesthetic from non-aesthetic may get thinner than one would like. And how a gifted poet may circumvent the socio-political milieu and, ignoring the lure of the officially sanctified Brahminical Sanskrit, carve out gems like ‘Ramcharitmanas’, ‘Vinaya Patrika’ and ‘Hanuman Chalisa’ in peoples’ language using folk metres and rhythmic patterns.

‘Hanuman Chalisa’ is an ode to Hanuman, the shy, devoted bhakt and servant of his lord Ram. Hanuman portrayed by Tulsidas is many things — an ocean of learning and virtues, a great, brave general who leapt confidently across the seas carrying his lord’s ring in his mouth and, above all, a man of unshakeable loyalty and faith. ‘Hanuman Chalisa’ that celebrated author, poet and travelogue writer Vikram Seth has translated is a slender collection of 43 rhymed couplets (two dohas, and 40 chaupais and a coda at the end, to be precise).

In a translation that has managed to grasp all the subtle nuances of bhakti and shakti, devotion and power, as Tulsidas perceived them, Seth has achieved the near-impossible and handed the readers a joyful and flawless translation from the original Awadhi into English.

Goswami Tulsidas lived on the steps of the ghats of Varanasi as an orphan and an outcast. He claimed to have been introduced to the Vaishnavite Ramanandi tradition by Guru Ramanand. It is entirely appropriate that the Bhakti cult Tulsidas grew up in, was brought to the north by Guru Ramanand from the south (“Bhakti Dravide oopji, laaye Ramanand”). Today, Tulsidas is best known for his Awadhi epic ‘Ramcharitmanas’, based largely on the Sanskrit ‘Ramayana’ by Valmiki, another orphan and outcast.

Seth, as translator, has taken special care to see that the alien language at no point drains the verses of the sonorous beauty of the dialect and purity of folk-rhyme patterns. Reading and re-reading the dohas in English, it’s also a relief to discover that in the act of recreating Tulsi’s invocation of Hanuman, the monkey god, Seth has distanced the ‘Hanuman Chalisa’ from all those aggressive overtones the public chanting of these couplets by crowds of hard hats had injected into them, while they sat on dharnas outside houses of those they deemed as enemies of Hindutva. Or simply to disturb the peaceful namaz being held within certain targeted mosques. Hopefully, the phonetic transliteration for those who cannot read the Devanagari script will help dispel any doubts such spectacles may have left behind, about what is a sonorous incantation of love and devotion of man for his lord.

Hanuman is the closest among his followers to Ram, as he tells his brother Bharat elsewhere, he will always be indebted to the monkey (“Bharat bhai, Kapi te urin hum naheen”). This had perhaps made ‘Hanuman Chalisa’ a predictable target for those who sought to present icons of Hindu religion as militant, avenging forces for destruction and segregation of human societies.

Vikram Seth’s transparent translation shows that poetry may yet create a space through thickets of time, confirming the core human values of love, compassion and trusted companionship between humans and humans and animals, between humans, animals and demons.

Excerpts of Mrinal Pande’s interview with Vikram Seth…

Why Tulsidas wrote ‘Hanuman Chalisa’ is understandable. Tulsidas related to Hanuman because, perhaps, both were underrated, low-key performers initially, unsure of their social bearings. They had immense hidden powers but they needed a mentor who would help them unlock those powers and make them perform tasks which were nothing short of miraculous. But why did you select this particular ode from all of Tulsidas’ poems? As you have mentioned in the introduction that it was maybe because your hero in ‘Suitable Boy’, Bhaskar, recited it. Or there was something more in your mind?

How much of Bhaskar is in me is a difficult question because any character has to have something of you in them if you’re going to give them life.

But I don’t think I chose ‘Hanuman Chalisa’. It was the other way round. I translated it as a labour of love and recited the translated version once in a very raw form at the Patna Literary Festival 10 years ago. After that, I just put it aside until my widowed 90-year-old aunt, who recites the ‘Hanuman Chalisa’ twice before she goes to bed, asked me to show it. And then she told me, ‘It’s very selfish. You should share it with other people.’

There are scores of minor intermediaries a good translator will use to rewrite the original in a language that he or she is proficient in. In Hindustani music, they have a word for it, Jod Raga, a set of notes common to two different ragas that is used as a bridge. To go from one raga to another, back and forth. What were your intermediaries?

The only effective intermediary for me were the rhythms: dactylic and trochaic rhythms, though not very common in English, they do exist. I managed to elide the rhythm of sort of ‘Jai Jai Jai Hanuman Gosai’ to “Hail, hail, hail Hanuman, great teacher’, to try to fit it in.

It’s interesting that the rhythms should speak to you and bring you to parallel sounding words, like in the 23rd chaupai:

“Aapana teja samhaaro aapai

Teeno(n) loka haa(n)ka te(n) kaa(n)pai

(You alone can control your own fire;

The three worlds quake

when you roar out your ire).

I could not get the nasalisation though in “Teeno lok hank te kaanpein”. It’s a lovely bit.

You have created a beautiful cover for it. The Nagari sits so well in gold letters against the red.

I don’t write in the standard Devanagari calligraphy. I use it like a Chinese style where you’re lifting the brush to go down onto the stroke so that you can tell what the stroke order is. It gave me a lot of pleasure to do that.

What sense or image of Tulsidas did you get while you were working on it? What did you feel about Tulsidas the man?

Tulsidas is a very vague figure. Even the ‘Hanuman Chalisa’ says, “Tulaseedaasa sadaa Hari cheraa keejai naatha hridaya maha(n) deraa…”

(Tulsidas, who will always serve you,

Prays, O Lord, in his heart to preserve you).

I see him mainly as the author of the ‘Ramcharitmanas’. He had other great works but this is his seminal work. Throughout North India, the Ramlilas and everything else is based on that. However, in ‘Hanuman Chalisa’, I didn’t have a sense of Tulsidas but a Hanuman in his elemental world. And also the poetry is incantatory and mesmeric. Even when Hanuman is doing a bit of violent Asura Samhara, or when he’s burning Lanka, somehow you just get the sense of his jumping around, doing fun things. Ram is rather a revered pious, distant figure here, and sometimes not even very empathetic in certain matters. But Hanuman, you just can’t not like him.

Another thing that surfaces again and again in the early poetry of Tulsidas, including ‘Vinaya Patrika’, is the feeling that he was an outcast. That he was lonely, clueless, powerless:

“Buddhiheena tanu jaanike,

sumirau(n) pavana kumaar,

bala buddhi vidyaa dehu mohi(n),

harahu kalesa bikaar …”

(Knowing how shallow my learning is,

to you, Hanuman, I pray —

Grant to me wisdom, knowledge and strength;

take every blemish away).

As a poet, Tulsidas feels that his mind is riddled with many worldly passions. So, in Hanuman, he perhaps discovers somebody who was similarly flawed, but rose when Jambvant told him:

“Jambvant kaha tumha saba layaka

Pathaia kimi saba hi kara nayaka

Kahesi reechhpati sunu Hanuman

Kaa chup sadh raheyi balvana” (‘Ramcharitmanas’)

(Jambvant, the king of bears, said to Hanuman, “Listen Hanuman, the powerful must not stand mutely. You are a totally reliable leader for

travelling to Lanka.”)

Probably that was Tulsidas’ intermediary moment.

I think that may be so. In other places also, you see that kind of hesitancy. He sees Hanuman as a teacher in a way as well, as an intercessor, as an intermediary, as a worker of miracles who has risen above his doubts.

The more you read into these verses and you read the English and the Hindi ones side by side, the more kind of possibilities emerge. And, many things come to mind. For example, the very first one,

“Shree guru charana saroja raj, nija manu mukuru sudhaari…”

The mind is dirty and like a mirror we clean it with charan dhool.

Another interesting thing is that in Hanuman, an ever anxious Tulsidas also finds solace.

Apart from writers, many other people see Hanumanji, and to some extent Ganeshji as well, as gods beyond the natural pantheon, as anthropomorphic gods who are more approachable, more humane perhaps. So they see Hanuman or Ganesh as someone who is more accessible to them, less daunting.

Even as children, we used to warm up to Hanuman much more after the annual Ramlila. Everybody tried to be a Hanuman, stick a tail and then hop around. Even while watching Ramlila, there’s something joyful and magical about Hanuman. How come you took 10 years to get this book published? And why now, especially when ‘Hanuman Chalisa’ has been politicised and weaponised very, very badly?

Well, it wasn’t that I tried to keep it depoliticised or sort of not anti any religion. Tulsidas himself does. The text doesn’t have anything sort of petty about it or self-aggrandising about it. And Hanuman is in the service of someone. He’s not there saying that I have a 54-inch chest or whatever it is. He is actually a devotee.

And the use of this thing, especially in the last few years, is clearly against the spirit, the better spirit of Hinduism.

In the lottery of life, if we happen to be born in one religion, it gives us absolutely no right to attack or demean other religions. And as Indians, we have Hindus, Muslims, whatever we are, even atheists, whatever that is, should not in any sense reduce our rights or our sense of patriotism, or our pride in our culture.

We have a wonderful culture which has Judeo-Christianity in it, which has Islam in it, which has Hinduism in it. We are one of those lucky countries in the world which has all this. To exclude something is to impoverish yourself and to weaken yourself.

I wanted to publish it actually on Hanuman Jayanti but then I thought, ‘Oh my god, the elections are coming up. It’ll get sucked into that. So I told my publisher, I’ll do it after the elections.’And even if Modi had come in with 400 seats or if the INDIA bloc had formed a coalition, this book would have been published on my birthday (June 20) anyway. And I wrote the introduction in November last year. It has nothing to do with the result of the election. Every word came long before. I want to keep it out of all this stuff.

It is a gem of a book.