Kulwant Roy’s images at Santiniketan: Life, in black & white

Sarika Sharma

In the 1970s, celebrated photographer Kulwant Roy was diagnosed with blood cancer, a disease then shrouded in mystery. Aware that the end would come soon, he began handing over his archive to Aditya Arya, a family friend and photographer. By 1980-81, he had given Arya almost his entire collection. Roy died in 1984, leaving behind a wealth of photographic history. Arya well remembers their last conversation. “One day, if you have time, go through them and you will find something interesting,” he had told Arya.

When that day arrived some 25 years later, Arya discovered a rich archive of history — of an India fighting to attain Independence, of its many heroes in their candid moods, the many firsts the country was to soon touch, the many ‘temples’ modern India was to raise…

Born in Ludhiana, Kulwant Roy trained at Gopal Chitter Kuteer in Lahore, a photo studio run by Arya’s maternal granduncles, which supplied photographs to The Tribune as well. At Lahore, and later when he opened a photo agency in Delhi, Roy saw history being scripted from those rare close quarters. And like a fine archivist, he kept his negatives safe. But time, fluctuating temperatures and humid conditions during those long years of storage had left cracking-like defects on the negatives. Arya had an uphill task at hand.

“There is always a right time, right place for everything. If I had opened those trunks earlier, I wouldn’t have had the resources; also, the word ‘digitisation’ had not come into being. There were no methodologies to salvage the photographs because we were still in the world of analog. It’s only in the late 2000s that people started talking about digitisation of images. By then, I had the resources to undertake that as well,” says Arya, known for his commercial and travel photography. “The negatives were like jigsaw puzzles. We assembled these on flatbed scanners and created images.”

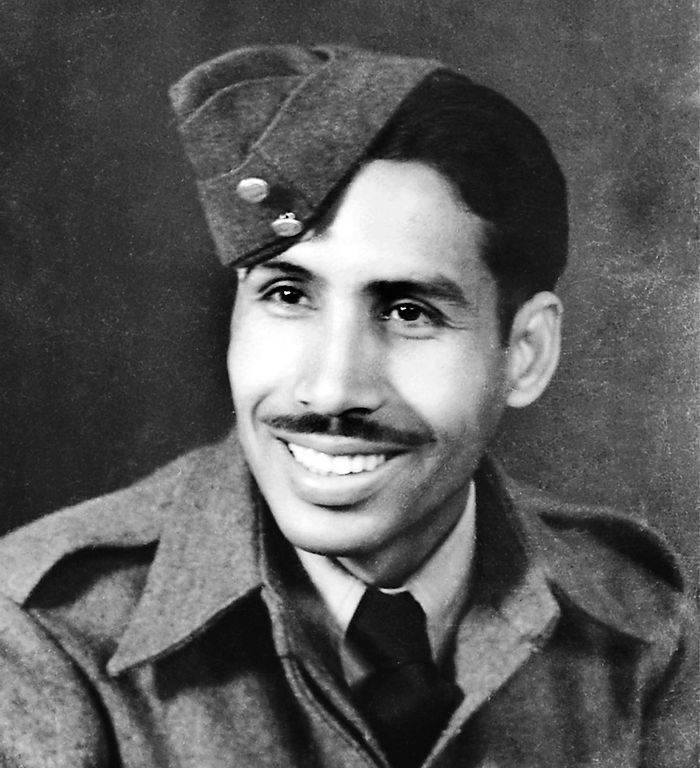

The world these images threw up was exceptional: Muslim League meetings, INA trials (among them a picture of INA soldiers singing ‘Kadam kadam badhaye ja’ before Gandhiji), the signing of the Indian Constitution, the building of Bhakra Nangal dam (depicting the scale of human effort behind the scientific marvel), besides others. Roy had travelled with Mahatma Gandhi, photographed Jawaharlal Nehru as a Seva Dal volunteer in Delhi, joined the Royal Indian Air Force, trained as an aerial lensman near Quetta…

Digitisation began in 2008, a process that turned fragile negatives into digital images. Over the years, thousands of photographs have been preserved; yet, as many remain. Around 80 are on display at Arya’s Gurugram museum, Museo Camera, one of the largest museums of photography in Asia. Nearly 75 of these are on display at an exhibition, ‘History in the Making: Visual Archive of Kulwant Roy’, being showcased at Arthshila in Santiniketan (West Bengal) till September 1.

A highlight of this exhibition is the postcards Roy sent to friends during his world tour from 1968 to 1972. “While on this tour, he was constantly clicking pictures and sending them to his photo agency. When he returned, the negatives were missing. Were they stolen? Were they hidden? No one knows what happened,” recalls Arya. Roy was heartbroken. He announced rewards in newspapers for anyone who’d return the negatives, rummaged through garbage bins in a futile attempt to find them. These postcards thus serve as verbal imagery of what he saw and how he saw. Written from places as diverse as Amsterdam to Geneva and Nagasaki, these are poignant glimpses into his experiences and the images that were lost forever.

Roy’s career trajectory could be divided into two phases, before and after Independence. “After 1947, his focus changed. His lens was now trained on building of a new India; instead of following Gandhiji, he was following pilgrims and travelling to various places. India was already an exotic place and his photo agency was supplying images to several international publications. Museo Camera has a wall dedicated to his images published in newspapers and magazines all over Europe,” Arya recalls.

Insisting on the urgency of archiving, he wishes that he had begun digitising Roy’s archive sooner. “Most of the analog material is reaching a point of no return. We have to preserve whatever we can for posterity.” His advice to those whose black and white family photos are decaying is clear: “Take them out of the albums, get them scanned and get digital copies made.” Lest it is too late.