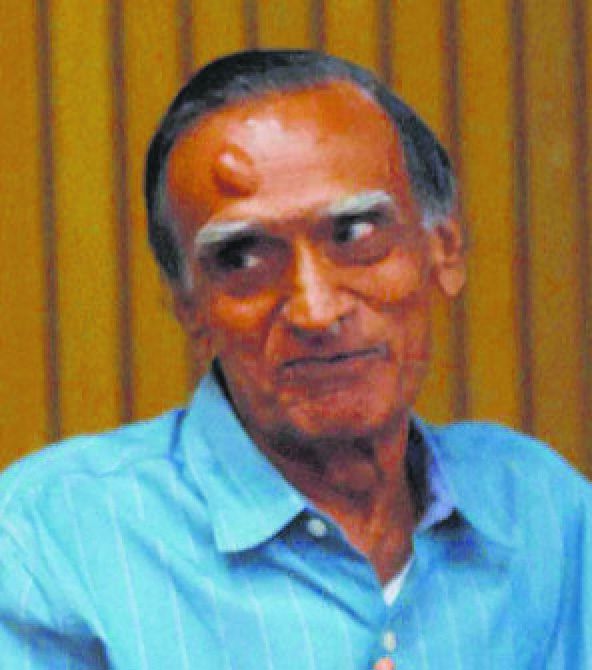

A tribute to Muchkund Dubey, the illustrious diplomat who was a class apart

Ramu Damodaran

Muchkund Dubey passed away on June 26, the 80th United Nations Charter Day. He was 12 when that foundational document was signed by 51 countries, including his still not Independent own. Less than three years earlier, his father had been imprisoned during the Quit India movement; he had awaited his return in the family’s single-room home, in today’s Jharkhand, on whose wall was written, in Sanskrit, “Do not come in my way. I can hear the fear in this terror-stricken world.”

The resolve to help assuage that fear led him to the Indian Foreign Service and the United Nations, as a delegate and an international civil servant. The breadth of possibilities he saw in fresh ideas was vast, as was his impatience when they were narrowed. In a memorable intervention at the United Nations in 1985, as Chair of the preparatory committee for the conference on disarmament and development, he said, without the least indication of irony, that the committee “has been able fully to discharge its mandate. In fact, it has gone beyond that mandate and made a series of recommendations on other vital aspects of the preparation for the conference”.

Nor did he acclimatise to laziness and custom in drafting. As a UN delegate in the Sixties, faced with an Eastern European proposal that “men and women should be equally entitled to maternity leave”, he suggested (a half century ahead of his time; it was a word determined by the UN in 2022) that it should be “parental” and not “maternity”. (Drawing raging rapier response from the Soviet delegate, the redoubtable Madam Furtseva, that it was astonishing that the land of Indira Gandhi and Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit should be represented by so chauvinist a male.)

That diplomacy demands anonymity of face, he proved wrong, aided by the Shakespearean actor mobility of his features. When he laughed, each nuance of his face’s cheer burst into good humour that was the little boy he once was in Jasidih. When he approved, his eyes and lips mellowed into gentle, gnostic grace. And when he was angry, every element of expression seethed. As did his writing on the world he lived in, where “the major powers that have exercised hegemony in the world order since the Second World War, along with their allies, started a concerted, planned and coordinated effort to weaken the United Nations and whittle down its role and functions”.

He saw that role as that of conscience, and arbiter of grievance and fear. Nations should feel free to approach it, nations that had nothing to hide should welcome the opportunity to state publicly their position in response. Not everyone agreed, nor will agree. When he headed the Foreign Office division dealing with Bangladesh, he accepted that country’s placing on the agenda of the United Nations First Committee (dealing, of all things, with global security and disarmament), in 1976, the sharing of the Ganga’s waters at Farakka, and the subsequent UN resolution which “urged India and Bangladesh to negotiate on this issue seriously with a view to finding a speedy solution”. Discussions with Dhaka did lead to an agreement with a concession that, in his phrase,“was regarded as a great achievement for Bangladesh. For India, it meant getting out of the way a recurring problem in dealing with one of our most important neighbours”.

My only opportunity to work directly with him was at the Harare non-aligned summit in 1986. He supervised our dealings with international organisations in the Ministry of External Affairs. I was a three-month-old cub in our delegation in New York. He invited me to dinner the first evening. As I reached to open my menu, he placed his hand on mine and said, “Leave it to me. Pretend you’re having dinner with Shankar Bajpai,” a reference to the legendary gourmand of the Foreign Service. The ‘tiger fish cutlets’ he ordered were as light as our initial conversation, buoyancy in every bite.

Suddenly, the tenor changed. “Have you ever watched tango?” he asked. I cautiously admitted I had. “It’s like international relations,” he continued. “You dance with one partner and think you have one partner alone. Then you look around the room and see so many couples, but all are in coordinated movement, moving clockwise or counterclockwise. And you are part of that much, much larger dance.”

“Nations,” he continued, “are persons. Not people. Each with her own likes, faiths, prejudices. And the qualities of warmth, of compassion, of understanding, that make us who we are.”

The restaurant had thinned and, declining dessert, we returned to our rooms. Our day was to begin early the next morning when the disarmament committee was to meet, with Dubey presiding and I in India’s seat — at least metaphorically, since there were no signs with country names.

It worked well, with a constant flurry of notes from him on the podium, to me in the hall, with instructions on what I should say, gamely carried by an agile Zimbabwean conference aide. Until a new aide came in. “Give it to the Indian man,” Dubey instructed. The aide looked around, zeroed in on his destination and handed the note to Pakistan’s delegate, Munir Akram.

Akram unfolded the paper and read it, a slow smile unexpectedly gentling his features. His eyes met the anxious Chair’s. He slowly refolded it, gave it to the Pakistan aide sitting behind him and asked that he bring it to me.

A nation had become a person.

— The writer is non-resident Senior Fellow at Centre for Economic and Social Progress, New Delhi