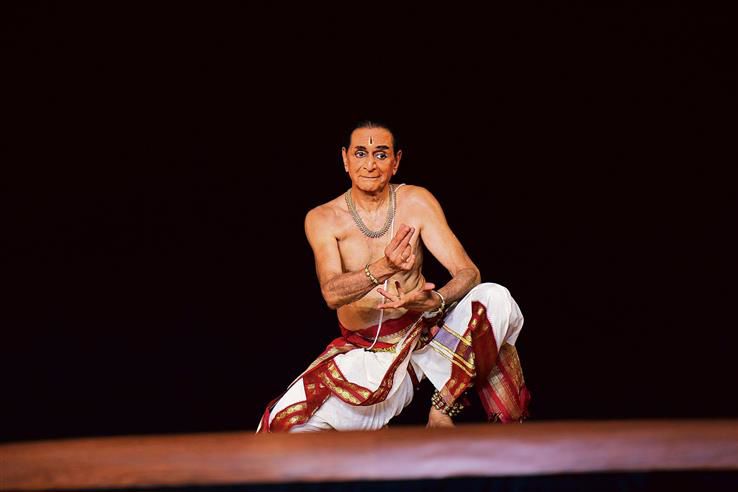

CV Chandrasekhar: Ambassador of Bharatanatyam

Sreevalsan Thiyyadi

The pine trees at Mussoorie reminded young CV Chandrasekhar of the hill-slopes in Shimla where he grew up as a child. The lanky artiste had just reached the Himalayan range, travelling 2,500 km from Madras. The metropolis was where the Tamil-origin boy learned Bharatanatyam, on the cusp of the country’s Independence, at the nascent Kalakshetra, where the classical dance was gaining fresh identity. Now in the Garhwal town that gave him a job, language was no issue. Chandrasekhar was fluent in English and Hindi his colleagues and students spoke at the boarding school. After all, Delhi was mostly where he had lived till age 10.

At Mussoorie’s Manav Bharati, Chandrasekhar taught dance along with a couple of other subjects. This lasted just a year. Varanasi became his next stop, with Chandrasekhar enrolling for a PhD in botany. A “misunderstanding” with the guide led him to discontinue research. That gave Bharatanatyam a full-fledged practitioner. At age 27 in 1962, he married a dancer-lawyer. Jaya Chandrasekhar, too, was cosmopolitan: born in Bombay, raised in Kanpur and ancestral Tamil Nadu, before shifting to the national capital.

For the couple, artistic life bloomed around Kashi. Chandrasekhar worked at Banaras Hindu University, while Jaya’s official tryst was with Rajghat Besant School on the outskirts of the ancient city. The family harmony showed in their penchant for co-opting North Indian aesthetics into Bharatanatyam. The husband and wife were getting exposed to Hindustani classical in a big way. The silken quality of the khayal concerts prompted Chandrasekhar to employ those ragas as background scores. He selected themes that suited the literary tastes upcountry. Soon, CVC and Jaya became the ambassadors of Bharatanatyam across the Ganga-Yamuna belt.

In any case, Chandrasekhar was exposed to Hindustani music as a kid in Delhi even as he learned the fundamentals of Carnatic. In 1945, when the Grand Trunk Express took him down south, his aspiration was to become a vocalist. Kalakshetra was studded with Carnatic maestros such as Mysore Vasudevacharya and Budalur Krishnamurthy.

Yet, the poetry sculpted by human movements lured Chandrasekhar into Bharatanatyam. After the first year, he became a dance student. A while later, Dagar brothers Moinuddin and Aminuddin happened to stay briefly in Kalakshetra. Chandrasekhar was enticed by the grandeur of their dhrupad. His capacity to converse in Hindi led the teenager to be the favourite errands boy for the titans all through their three months at Adayar. Their reposeful alaap and pakhawaj-assisted invocations found resonance in Chandrasekhar during his 30s at Varanasi. When he danced on stage, Jaya sang. And vice versa. The partnership gifted Bharatanatyam with 20 milestone productions.

Their works evolved also in the country’s west, as CVC and Jaya shifted to Gujarat, concluding Chandrasekhar’s 25 years of BHU association from 1954. For 12 years from 1980, MS University in Vadodara became his creative studio. From Bhojpuri to now Gujarati, the linguistic change prompted Chandrasekhar to experiment in a spectrum of subgenres. “Any art keeps changing, however slowly and subtly,” he used to say.

For CVC, thorough knowledge of the ancient ‘Natya Shastra’ treatise was not important to imbibe the spirit of classical dance. Towards the end of the century and aged 65, Chandrasekhar chose to return to Madras, which had by then got renamed. At Chennai, he set up Nrithyasree. His mentor and Kalakshetra founder Rugmini Devi Arundale (1904-86) was no more; so were chief gurus K Saradambal and Dandayudhapani Pillai. The Bharatanatyam repertoire had grown multifold since the second half of the 20th century. Chandrasekhar would fondly recall his nine years (1945-54) in Kalakshetra, which also let him undergo college education.

“I was into my fourth year of dance, when atthai (Rugmini Devi) suggested the idea of my debuting on stage,” the Padma Bhushan awardee would say. Excited but cautious, he presented the Todi-raga varnam Rupamu joochi as the centrepiece on the campus in 1950. A lot of buffs and scholars had turned up for the show, curious about the rare sight of a boy dancing. Those were days when the males largely remained tutors for girls doing Bharatanatyam.

Staying engaged had been “very important” for CVC. As danseuse-actress Vyjayanthimala notes, Chandrasekhar, who died on June 19, maintained “highest standards, never compromising”.