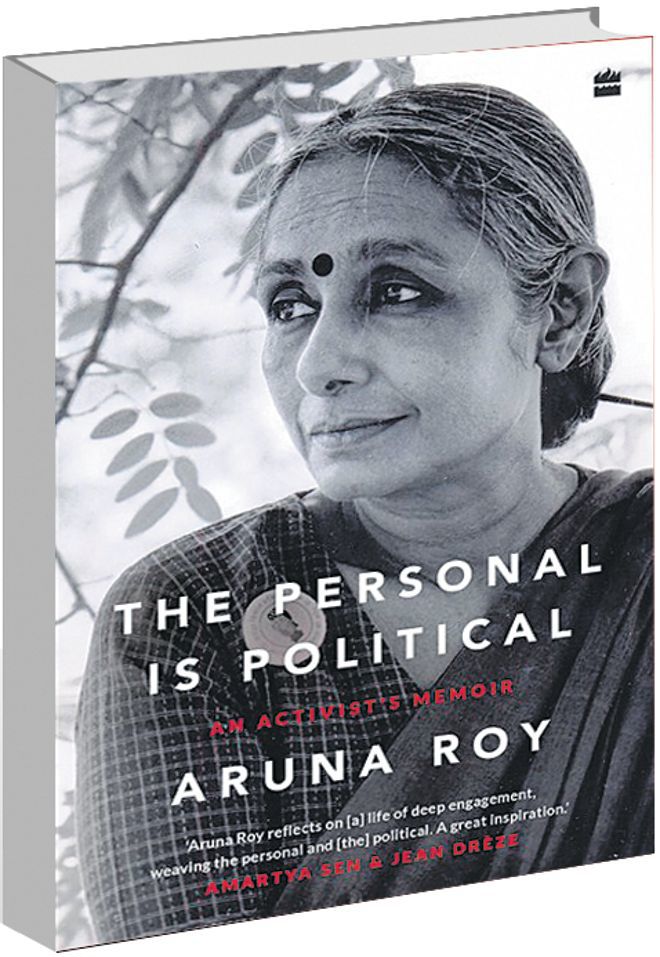

The enduring Roy of hope: ‘The Personal Is Political’, activist Aruna Roy memoir

Ira Pande

The title of the book is both evocative and mysterious: is this a personal memoir of one of our most admired public activists, or a political statement of sorts? Before I go any further, let me put in a disclaimer. Aruna and Bunker Roy have been our friends ever since we got to know them in the late Seventies in Chandigarh, and they had just started their work based in Rajasthan’s Tilonia. In those days, while Bunker was training barefoot engineers to provide village-level technology that would ease the life of villagers, Aruna began coaxing the women to work with textiles and make bags, cushion covers and stuffed toys that were strung as mobiles for babies. I used to joke then that our home in Chandigarh was like their showroom: our curtains, diwan covers, the kathris that our babies slept on — all these were generous gifts given to us by Aruna.

How far away those innocent times seem now. Bunker was a dashing dude then: fresh from St Stephen’s College and a national squash champion. Members of his distinguished family were peppered all across the world and it seemed to us wide-eyed admirers that there wasn’t anyone he did not know on a first-name basis. Aruna, the quieter of the two, had her own remarkable history. She had quit the IAS (at a time few had the courage to do so) to start work in a remote desert area with women who still wore veils, and were deeply suspicious of one who roamed around without one. I can only imagine what it must have been for the two of them to live without the comforts of electricity and running water, in a rough ‘home’ with the bare minimum to ease their life.

This book draws a veil over those personal hardships and the challenges of that life: both Bunker and Aruna had long ago subsumed their individual lives into that of a larger community, so readers who seek such information may feel disappointed. What the book does emphasise is that in order to effect change, one must become that change. It was Gandhiji who first gave us this mantra and as an old folk saying puts it: ‘Jaake pair na pari biwaayi, woh kya jaane peer parayi.’ Roughly translated, it means, ‘How can one understand another’s pain if she has not suffered cracked and bleeding heels?’ Gradually, as this book reveals, Aruna managed to break through the layers of suspicion and sullen disbelief.

The encounters of these villagers with the sarkar had bred in them a healthy contempt for anyone who promised them anything. The reader will meet many characters in this book, like Naurti, Mangi and Billan, who became active participants in protests against rape, sati, female infanticide. Once their tongues were loosened, there was no stopping them. Their confidence in themselves and their collective strength asked the arrogant and feudal system questions that it was unable to answer.

“Working class women’s politics was taught to me,” says Aruna, “by these ‘professors’ who knew and articulated the thought in an idiom much more compelling and communicative than mine could have been. They stated their own limitations and made me see and accept some of mine.”

It will become evident soon enough that this was a two-way education. Aruna brought them a world of the outside and they gave her insights that had the strength and honesty of lived experiences. How right Gandhiji was when he said all those years ago that before you take a decision, think of the poorest man you know and ask yourself how this decision will affect his life. Aruna brought enormous change in the lives of these sequestered and hidden women. Yet, equally, she has been radically reformed by her own work amongst them. Her work in the Right to Information, MNREGA, Right to Education et al, got her the prestigious Magsaysay Award, but her true achievement was to focus attention on the rights of people whom we had forgotten to factor in when making high-minded policies.

This glaring mistake that all governments have been guilty of committing has been highlighted in the recent elections, where the common man has trumped the uncommon and privileged person. Never again, I hope, will this salutary lesson be forgotten when drawing plans for the nation’s progress. For, until the fruits of economic progress reach the last Indian, economic progress will be like building a fortress on a bed of sand. Again, Aruna’s mentoring of a dedicated band of like-minded workers is something that must be followed by other activists. Long after she and Bunker retire, they can rest assured their followers will continue the good work they have laid the foundation for.

I finally understood why the book is titled ‘the personal is political’; there is no other way to live a meaningful life.