The word Phulkari is synonymous with Punjab and its culture. Its relevance, in the lives of the people, has not diminished even today and continues to form an integral part of all marriage ceremonies taking place in Punjab. In the past, as soon as a girl was born the mothers and grandmothers would start embroidering Baghs and Phulkaris, which were to be given away at the time of marriage. Depending on the status of the family, the parents would give dowry of 11 to 101 Baghs and Phulkaris.

Ih Phulkari meri maan ne kadhi/Is noo ghut ghut japhiyan paawan (This Phulkari was embroidered by my mother, I embrace it warmly).

Folk songs like these are indicative of the emotional attachment the girl had to the Phulkari embroidered by her mother or grandmother, or aunts.

The floral work

Phulkari literally means floral work as the entire field is embroidered and filled with flowers. This word first appeared in Punjabi literature in the 18th century. Waris Shah's Heer Ranjha describes the trousseau of Heer and lists various articles of clothing with Phulkari among them.

There are different theories about the origin of Phulkari. One such belief is that this embroidery was prevalent in different parts of the country as far back as the 7th century but survived only in Punjab. Motifs similar to the ones found in Phulkari are also found in Kashida of Bihar and some of the embroideries of Rajasthan.

Another thought is that this style of embroidery came from Iran where it was called Gulkari, also meaning floral work.

Flora Anne Steel (1847-1929) lived in India for 22 years as Inspector of Girls Schools in Punjab. She was, perhaps, the first to study Phulkaris of Punjab. In one of her articles, published in 1894, she puts forward another theory about its origin. She writes, "It seems indubitable that wherever the stalwart Jat tribes of the south-eastern plains came from, with them came the original Phulkari workers; for the art, almost unchanged, lingers still in its best form among the peasants of Rohtak, Hissar, Gurgaon, Delhi and to some extent in Karnal".

Phulkari was essentially a product of domestic work done by the women of the household. Despite the fact that this embroidery was not done on a commercial scale, some of it did find a market abroad. Lockwood Kipling (father of Rudyard Kipling) prepared a report on Punjab industry for the Journal of Indian Art. He writes, "Since the Punjab Exhibition of 1881, a considerable trade has arisen at Amritsar, where in the neighbouring villages, women of nearly all castes occupy their leisure in this work. Industrial and Mission schools have succeeded in producing Europeanized versions of Phulkari of quite astonishing hideousness and it may be said that more primitive the district the better the work". While the women of Punjab used these embroideries for shawls, or ghaghras, they were used to make curtains for European homes. Specimens of Phulkari cloth were sent to Colonial and Indian Exhibition, held under the British regime, from different regions of Punjab, mainly Amritsar, Sialkot, Montgomery, Rawalpindi, Firozpur. There were firms in Amritsar where Phulkari work of any shape or size could be ordered. Devi Sahai and Chambamal or Devi Sahai and Prabhu Dayal sold ordinary chaddars ranging from Rs 5 rupees to Rs 20.

The lost glory

By the end of the 19th century, Phulkaris and Baghs had found a market in Europe and America. Some of the firms procured orders from Europe for supplying Phulkari on a commercial scale. The newer market dictated the changes in designs and colour combinations. Flora Anne Steel, too, in her paper on Phulkari condemns the blatant commercialisation of the craft and refers to the changes that this brought to the simple rustic embroideries of Punjab.

Sir George Watt in the 1903 catalogue of “Indian Art at Delhi” confirms that while in Ludhiana, in connection with the exhibition, he was shown a consignment of several bales of Phulkaris, that were ready to be dispatched to America. The dealer had shown him the pattern, which had been furnished to him by a European trader. He observed, "…that it paid him to make such stuff but he could not see what the people in America thought beautiful or found useful in these monstrosities in black, green and red embroideries. The design was not Indian at all and the stitches of embroidery were fully an inch in length". Flora Steel also talks about the deterioration of the embroideries. "Already the native women look at some of my most cherished treasures critically and remark; those must be very old; we don't work like that nowadays". The exhibition had exhibits from Rohtak, Hissar, Sialkot, Amritsar, Lahore and Rawalpindi.

Balancing the materials

The fabric on which Phulkari embroidery was done was handspun khaddar. Cotton was grown throughout Punjab plains and after a series of simple processes it was spun into yarn by the women on the charkha (spinning wheel). After making the yarn it was dyed by the lalari (dyer) and woven by the jullaha ( weaver)

The fabric was woven in widths, which were narrow, as the width of the loom was such. Thus, the fabric had to be stitched lengthwise to make the desired width, which was later embroidered. This practice of stitching two pieces was common among textiles of Punjab in the early 20th century. Textiles like khes were also stitched lengthwise. In West Punjab (now in Pakistan), sometimes joining was done later, leading to distorted designs. Madder brown, rust red or indigo were the usual background colours for a base for the embroideries. Soft untwisted silk floss called pat, was used for embroidery. The thread came from Kashmir and was dyed in the big cities by the lalaris. The village ladies obtained the thread from hawkers or peddlers who sold things of daily needs, from village to village.

The variety

On the basis of the type of work, patterns and style Phulkari can be broadly categorised as Phulkari, Bagh and Chope.

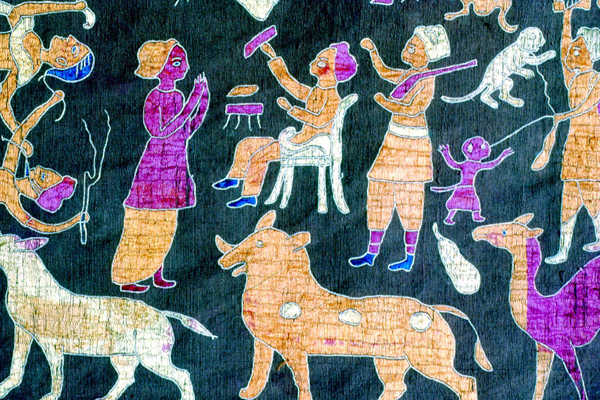

Phulkari is the kind of embroidery, which does not fully cover the fabric with embroidery, the patterns are dispersed at intervals on the cloth. One such style called Sainchi Phulkari has figures embroidered throughout its field. This is the only style where the outlines of the figures were drawn using black ink. It was then filled by embroidering with darn stitch. In other styles, there were no patterns drawn and the work was done only by counting the threads from the back. Sainchi was popular in Bathinda and Faridkot districts. It depicted various scenes of the village life.

Bagh (meaning garden) is a style wherein the entire surface was embroidered. By working with darning stitch numerous designs were made by use of horizontal, vertical and diagonal stitches. There were many kinds of Bagh depending on its usage like ghungat Bagh and vari da Bagh. Some were named after the pattern like Velanian da Bagh, bawan da bagh, nazzar buti, bhool bhulaiyan, dabbi and parantha Bagh. In many cases the designs were inspired by what the embroiderer saw around them.

Chope was embroidered on red with yellow. Two fabric panels were joined that had similar patterns embroidered on both ends. The only motifs embroidered on both selvage were a series of triangles with the base towards the selvage and pointing inwards. The design was worked with small squares in a step-ladder fashion.

The workshop of memory

There were no pattern books and embroidery was worked entirely from the reverse of the fabric. Traditionally, use of coarse khaddar fabric made it easy to count the yarn. The hallmark of Phulkari is, making innumerable patterns by using long and short darn stitches. The designs were not traced. Techniques and patterns were not documented but transmitted from word of mouth and each regional group was identified with the style of embroidery or design.

Phulkari in its original form has disappeared, though some revival is taking place at individual level with no help from the government. There are only a few designs of the Bagh, which are copied by workers today. Some styles like Sainchi, Phulkari and Chope are not reproduced anywhere in Punjab. It is important that the craft traditions are kept alive, but they would only be done if there is a demand for them. The remedy lies in reinventing the embroideries in styles, which are contemporary in look and follow the traditional techniques. This has been done by many states to keep their traditional techniques alive; Patola of Gujarat, Ajrakh printing of Rajasthan, Paithani weaving of Maharashtra, Kalamkari of Seemandhra etc. Punjab too can do it.

Threads of life

- Darshan Dwar was a type of Phulkari which was made as an offering or bhet (presentation). It had panelled architectural design. The pillars and the top of the gate were filled with latticed geometrical patterns. Sometimes human beings were also shown standing at the gate.

- Sainchi embroidery drew inspiration from the village life. Embroidering household articles and themes like man ploughing, lying on charpoy, playing chaupat, smoking hukkah or guests drinking sherbet were commonly embroidered. Domestic chores of women, such as churning the milk, grinding the chakki-hand mill, playing the charkha were also common topics. Women also embroidered scenes which they found interesting, like the scene of a British officer coming to a village; the women carrying umbrella and walking along with memsahib, scenes such as railways, circus as well as scenes from popular Punjabi stories like Sohni Mahiwal, Sassi-Punnu were among popular themes.

- Kitchen provided the designs of many Bagh — Belan Bagh, Mirchi Bagh, Gobhi Bagh, Karela Bagh, Dabbi Bagh. Whereas Dilli Darwaza, Shalimar Char and Chaurasia Baghs revealed the layout of well- known Mughal Gardens.

- Phulkaris from Hazara were mostly done on white cotton with purple and green silk and had different types of stitches.

- Sheeshadar Phulkari had inserts of circular pieces of mirrors embroidered with button hole stitch to keep them in place.

The writer is a textile researcher.