The man behind the iconic Jallianwala painting

Vishav Bharti

Tribune News Service

Amritsar, April 2

“Did all these men die? They killed the children too? Where are their mothers? Was General Dyer so bad?” a four-year-old girl, overawed by the imagery of the bloodbath, leaves her mother groping for answers.

It’s been five decades and Jaswant Singh’s celebrated painting at the Jallianwala Bagh Martyrs’ Gallery never fails to evoke similar questions.

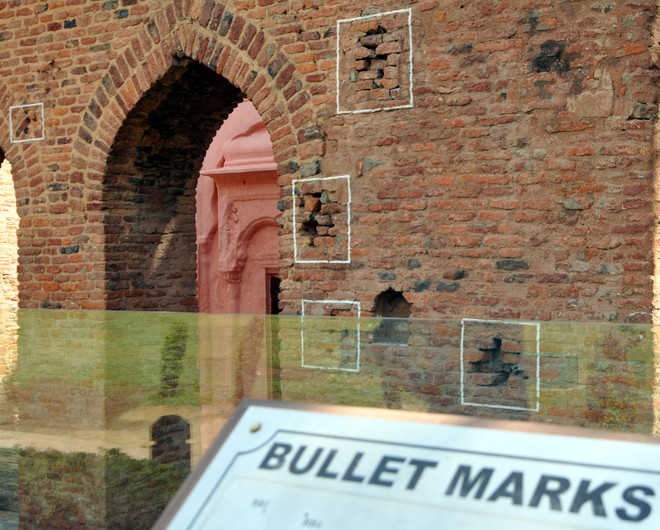

It depicts almost every tale generations of children have been raised on. A long row of soldiers in olive green, an officer with a stone face pointing at the people, the blazing .303 rifles making no distinction between the old and the young, between Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs, their struggle to scale the walls, the last resort of jumping into the well. And finally, a peaceful gathering reduced to a heap of corpses.

The story of the painting dates back to the 1970s when during a visit, civil servant Dr MS Randhawa witnessed chaos in the reception room of the Bagh’s caretaker and planned a museum, says Dr Anantdeep Grewal, a resource person at GCG, Chandigarh. “Dr Randhawa’s belief in the impact of visuals in understanding history is personified in the Martyrs’ Gallery at Jallianwala Bagh,” he adds.

Several artists were invited to send sketches on the theme. “Even doyens like Pran Nath Mago had sent sketches, but Jaswant Singh’s work stunned everybody,” says Chandigarh-based artist Prem Singh, who had a long association with the painter.

Almost five decades later, the painting has started showing signs of wear and tear. Some time ago, the Jallianwala Bagh Trust had approached local artists to restore it. However, Prem Singh says, “The work was certainly not one of Jaswant Singh’s best. He will always be remembered in art circles for his ‘Ragamala’ paintings.”

Not many know that Jaswant Singh, who hailed from Rawalpindi, started his career by painting roadside milestones on the Panja Sahib-Jhelum road. His father, who worked with the British Indian Railways, wanted him to follow suit.

“But he was not cut out for a job in the Railways. In his teen years, he came to Lahore, but soon the pace of the city threw many challenges his way. He started painting milestones to earn a living,” recalls Prem Singh. In beautiful calligraphy, he used to write the names of villages and towns located along the road from Panja Sahib to Jhelum.

Soon, he began working with a painter in Lahore, where he started designing book covers. “He became friends with Sobha Singh, Abdur Rahman Chughtai, Amrita Pritam and Rajinder Singh Bedi,” says Prem Singh. After Partition, he settled in Delhi, where he worked as an illustrator for weekly magazines.

Prem Singh fondly remembers that Jaswant Singh, who passed away in 1991, would often say that his imagination did not soar high in commissioned works. “Despite the shortcomings of a commissioned work, the Jallianwala Bagh painting influenced the masses,” he says.

Tomorrow

The books that were banned