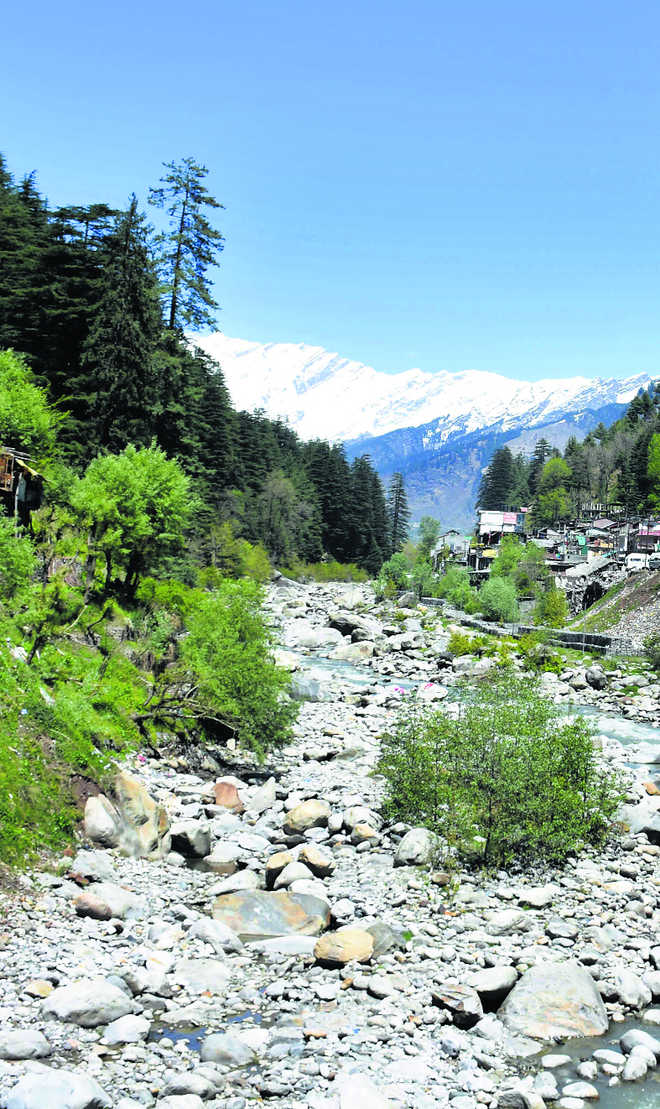

A trickle is all that remains

Pratibha Chauhan in Shimla

The unmindful tapping of rivers for hydro-power projects is swallowing them up, thereby impacting the biodiversity along the banks and livelihoods of the locals. Even as the demand for declaring many of the rivers, especially in the Trans Himalayan region, as “no go rivers for projects” grows louder, the government seems keen to harness maximum possible “power” as this is a major revenue generator sector for the cash-strapped state.

Vast stretches of the Sutletj river in Kinnaur and almost 6 km of the Beas in Kullu district have been diverted through tunnels, leaving a mere trickle of 15 per cent discharge in the river course. “With the river beds drying up, the life of the locals is being affected in a big way and the biodiversity is being ruined,” says RS Negi, a retired IAS officer who has been voicing his concerns on the adverse environmental impact of unregulated hydro-power generation in the ecologically fragile Kinnaur through the Him Lok Jagriti Manch.

The adverse impact of these projects — like major landslides, water seepage, drying of water resources like springs and flash floods — are all too visible across the state. Experts are seeking complete moratorium on new hydro-power projects till the process of preparing the action plan and holding Cumulative Environmental Impact Assessment (CEIA) studies for all the river basins is not complete. Demands are also being raised to declare highly polluted rivers like Sutlej, Ravi, Beas and lower stretches of the Yamuna as project-free.

A study by Himdhara, an NGO, has indicated that the rivers face key threats from activities that are detrimental to their very existence. These include indiscriminate exploitation of hydro-power, sand mining, mindless tourism promotion and haphazard and unregulated urban growth. Even though discharge from the power projects has been fixed at 15 per cent, there are violations too often.

Himachal has five main rivers basins of Sutlej, Yamuna, Chenab, Ravi and Beas. The Yamuna passes through the southeastern parts of the state; its two tributaries, Tons and Giri, originating in Himachal, merge into the Ganga basin. The other four rivers are major tributaries of Indus. Himdhara, an Environment Research and Action Collective, undertook a study to assess the threat projection to these rivers in the categories of critical, moderate and low. The report suggests that Ravi, Beas, Sutlej and Yamuna are the most threatened river basins. “It is only Chenab, and upper Sutlej, mainly the Spiti river and some parts of the Beas, like the Tirthan, which can be categorised as wild and free flowing,” says Manshi Asher of Himdhara.

The rivers also face a major threat from industrial pollutants, effluents and sewage, especially in the industrial hubs of Baddi-Barotiwala-Nalagarh and Paonta Sahib. Out of a total of 256 water monitoring points, 20 falling in these industrial areas are critical. “We feel there is an urgent need to prepare an action plan to protect our wild rivers,” stresses Asher.

Government intervention

Though no separate action plan has been prepared for the river basins, steps are being taken for treating areas impacted by the projects under the Catchment Area Treatment (CAT) Plan. The Cumulative Environment Impact Assessment (CEIA) of Chenab basin has been completed and submitted to the Ministry of Environment and Forest (MoEF). The draft final report of CEIA of Beas basin has been submitted too and is likely to be completed this year. The CEIA study of the Sutlej basin has been completed for all projects above 10 MW, but, on the directions of MoEF, it is now being done for projects below 10 MW also. The CEIA of Yamuna basin is likely to be taken up jointly with Uttarakhand, while in case of Ravi basin, the work is likely to begin this year. — Tarun Kapoor, additional chief secretary, power and environment