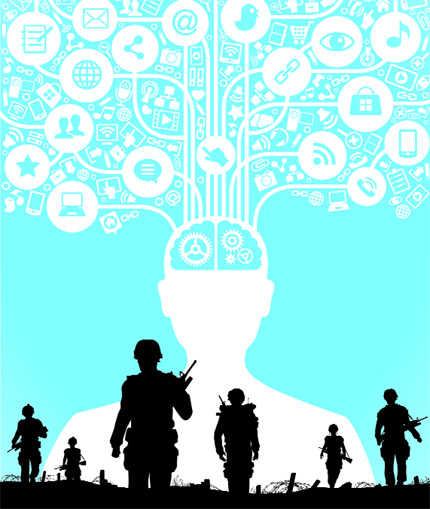

Why social media is Army’s new front

The social media has emerged as the new battlefront for the Indian armed forces. When its peacetime station at Samba, close to Jammu, was attacked on September 26 last year, just three days before India-Pakistan talks were to begin, the Army put out a version on how the armoured unit’s second-in-command had lost his life. Within days, however, a message on WhatsApp went viral — there were no casualties in the officers’ mess simply because the routine had been changed as the unit was due for an exercise the following day. The second-in-command died as he had gone home for lunch and was caught in a barrage of automatic gunfire from the terrorists as he rushed to the guards’ room for weapons. Further mayhem was prevented because soldiers from the adjacent 2 Sikhs joined the 16 Cavalry men in cornering the terrorists. Their end was swift because of the fortuitous presence of tanks with live ammunition for the exercise.

In the next attack at the Army’s Uri camp, six terrorists were swiftly eliminated but extracted an unusually high toll of eight soldiers. “They came and banged against this position of ours and all the six terrorists were neutralised. The security grid has succeeded but with a heavy price,” the Army’s 15 Corps chief, Lt Gen Subrata Saha, told reporters. But WhatsApp soon had a different version. “As per reports, soldiers on sentry duty did not fire upon the approaching terrorist vehicle due to caution imposed on them after the Anantnag incident. When the Anantnag incident took place, top officials had called it a mistake. Shouldn’t they consider resigning for this goof-up [heavy toll of soldiers]?” read the message circulated, probably by a junior officer. In Anantnag, the Army had fired on a vehicle killing two youngsters, which senior officers admitted was a case of mistaken identity.

Harnessing power of the medium

In Bangladesh, an Army Major serving with the Indian High Commission was trapped by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) via Facebook. Luckily, he confessed to his superiors and was whisked out overnight before he could damage his career or the country’s security.

If the Army had stuck to its conventional mode, it would have tracked down the electronic trail from the officers to their wives to one of their acquaintances in the media and disciplined them.

But the Army has understood the power and reach of the social media, and its beneficial effects of conveying the work it does in out-of-sight locations and against heavy odds to the people at large, much better than many other organisations. Its Facebook page — administered by the Additional Director General of Public Information (ADGPI) housed in the basement of the Defence Ministry’s stately South Block office — is the worldwide leader among government organisations in PTAT or “People Talking About That”. The more visible US army generally scores less than one-third PTATs as compared with the Indian Army.

The Indian Army’s Facebook page has an army of 21 lakh followers within 18 months of its debut though the spike took place after it spiced arid press releases with rare pictures of the 1971 war with Pakistan, which most Indians still consider as the high point of national stature of Independent India. It also started a “Great Battle series” in which the Army as an institution played a valiant role. The Army’s debut on Twitter was equally sensational. It has 3,45,000 followers.

Army as an institution gets responsive

The more-than-impressive debut of the Army’s public face on social media and the withholding of retributive action against individuals who, unaware of the consequences, posted alternative versions of the Samba and Uri attacks were helped by its understanding how it could harness its potential. The ADGPI is headed by an officer of the rank of Major General, who a decade back was a young Colonel in what was an out-of-the-way dank basement. Carved out of Military Intelligence, ADGPI was then fighting a turf war with the Defence Ministry’s civilian public relations setup, which would track and caution journalists trying to meet ADGPI officers. Even the official Army Public Relations Officer at that time would ignore or berate mediapersons he felt had met ADGPI officers without his consent.

The Army also had to face uncomfortable moments during the initial days of the social media when its officers and soldiers in uniform would proudly send pictures taken against the background of tanks and missiles to their folks back home.

Even earlier, when a mobile phone had not yet become a smartphone, a drive down the highway in Jammu and Kashmir and Manipur where the Army protects bridges and critical public offices, soldiers could be seen in the rather unedifying posture of cradling the phone between their shoulder and ear while the rifle hung loosely from the arm.

Changing profile, emerging tech

The years between 2000 and 2004 were also the time when India’s socio-economic profile was changing fast. A breakdown in the soldiers’ family structures was leading to strains and this was being conveyed to them in realtime to their field positions in counter-insurgency zones, where they were already under stress.

Leave to sort out problems was an issue. Suicides and killings of superiors by soldiers sandwiched by the problems at home but unable to resolve them and burdened by the pressure of counter-insurgency operations crossed the Army’s informal red line of 120 such deaths annually. The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO)’s Defence Institute of Psychological Research identified the use of mobile phones as one of the catalysts.

The Army didn’t immediately issue an edict banning the use of mobile phones but went about setting its house in order to meet the changed requirements of its personnel. It recognised that patrolling in forward areas in extremely difficult terrain with the possibility of an ambush just round the corner or from a hilltop was mentally weighing down soldiers. A call from home asking him to return and resolve issues with a disobedient child, a warring wife and her in-laws or encroachment on his farmland further boosted stress levels. The breaking point was reached when he was refused leave, leading him to take his own life or that of the official he thought had refused to understand his predicament. Among the corrective measures were the Army asking officers to fraternise more often with soldiers to increase internal cohesiveness, hold counselling sessions and sensitise the junior commissioned officers (JCOs) to reach out to soldiers showing signs of great stress and send them for specialised counselling. Men still resort to suicides, but the rate of such incidents has reduced. The approach, also followed by other armies worldwide, has been more effective than banning the use of the mobile phone.

Now, no soldier on patrol can carry a mobile phone, says a commanding officer of an infantry battalion. But the patrol commander is allowed to have one and the number is usually known to the families of the soldiers on patrol with him. The same routine is followed for soldiers on guard duty along highways, who tend to use mobiles more often because they have more time to themselves.

Individual liberty vs institutional ethics

Now that the talk-and-SMS instrument has evolved into a smartphone, the use of social media is being taken head-on. According to an Air Force officer, which like the Army also faced the problem of leakage of sensitive information because of men posing against equipment, the solution was simple — a complete ban on such photos. “We have issued lots of instructions and our men are now aware of that. No one can say they didn’t know about not being supposed to get a picture clicked when posing with air defence missiles or a fighter aircraft in the backdrop. Our services have also asked them not to pose in uniform,” he said.

The ban on senior officers not to pose in uniform is disputed, but followed. “I don’t think there is a need for such instructions. There are 10,000 Colonels in the Army and those whose business is to keep track, know the location of every cantonment. It really doesn’t matter if I get clicked in uniform in a cantonment,” he said. “But generally, people now are very careful about what they upload. A large percentage of them follow the instructions, but not all of them do so.”

Another officer referred to a spate of anti-Army messages on social groups. These are generally people who are part of social media groups of a particular batch of National Defence Academy or Indian Military Academy but have left the service. Several posts against “VIP culture” that found their way into the larger public domain were traced to them. Then there are social groups of soldiers or Army wives from where information about discord within a unit is leaked out.

Lt Gen SS Mehta (retd), the former Western Army commander, puts things in perspective: “Since the social media provides the link between hierarchy and individual behaviour, the sender of the message wears two hats — his and that of the institution. As the recipient doesn’t know who the sender is speaking for, there must be a link between the individual and institutional propriety. The social media is growing and when used by individuals with an I-me-myself approach, it could damage an institution with a heirarchical structure and collective ethos like the Army. Its members should utilise it keeping in mind institutional propriety and values.”

According to the current ADGPI, Major General Shaukeen Chauhan, the answer cannot be banning social media. “You can’t fight technology. How can you go backwards? Technology won’t permit this. Delinking men and officers from a particular social media means the platform will make them go in for alternatives. Our way is education. We send instructions to make them aware of the pitfalls of connecting through social media. Only by education do you make armed forces personnel aware of pitfalls,” he points out.

“The Army is seized of the adverse effects of social media. The best way is to educate officers and soldiers so that they don’t get trapped,” he reiterates.

'As an officer, I have been taught that the honour, welfare and security of the country comes first. People you command come next. Your own honour and safety comes after that, always and every time. Therefore, the various aspects of social media are worthy of a wider debate,” observed Lt Gen Mehta.

Flooded with messages for help during floods

The Army’s Facebook and Twitter ventures hit pay dirt when there was a communication breakdown in Kashmir valley last year. Civilians in danger of being swept away by the flood waters appealed directly to the Army’s Twitter and Facebook accounts. Others sought information about their friends and relatives stranded in floodwaters and unable to communicate to the outside world. The Army made sure it responded to each message — it reached out to those seeking succor with food or evacuation and informed those wanting to know about their acquaintances stuck in the floods, but with no means to communicate.

| Armymen rescue a girl from her flooded house in Srinagar on September 10 last year. Floods and landslides triggered by days of rain had wreaked havoc in the Valley. REUTERS |

HOW THEY DEAL WITH NEW AGE MEDIA

UNITED STATES army

Wearing just a bikini, the Facebook profile of Robin Sage described her as a cyber analyst with the US Navy. She attracted hordes of “friends”, including senior intelligence officers, four star generals and officials of defence companies developing sensitive technologies. But she was anything but that. Robin Sage was an exercise to ascertain how many serving US servicemen were attracted to the profile of an unknown person. This non-existent “cute girl”, as per her profile, is cited in the US army’s list of instructions on dealing with the social media by serving soldiers and their families.

“Be cautious when accepting friend requests and interacting with people online. You should never accept a friend request from someone you do not know, even if they know a friend of yours. For more on this, check out this article about the Robin Sage Experiment: ‘Fictitious femme fatale fooled cyber-security’,” says the second of the six broad guidelines given to all soldiers. Others deal with online social conduct, penalties on violating them, educating soldiers on privacy settings, sensitising their families and on what not to post.

British army

Like the US army, it faces the impact of up to 10,000 daily Twitter posts by the Islamic State. Earlier it was the Al Qaida and the Taliban who would often post images of US and British army soldiers being tortured or worse. Both armies as well as others involved in the conflict in the Middle-East now have large social media units to blunt the impact of these Twitter posts and Facebook feeds on the morale of their servicemen. In addition, it tells soldiers about “several sensible precautions” they must take while using social media platforms because journalists, terrorists and hostile intelligence agencies trawl the Net to “conduct their business”.