Tracking Indian troops to trenches

Sarika Sharma

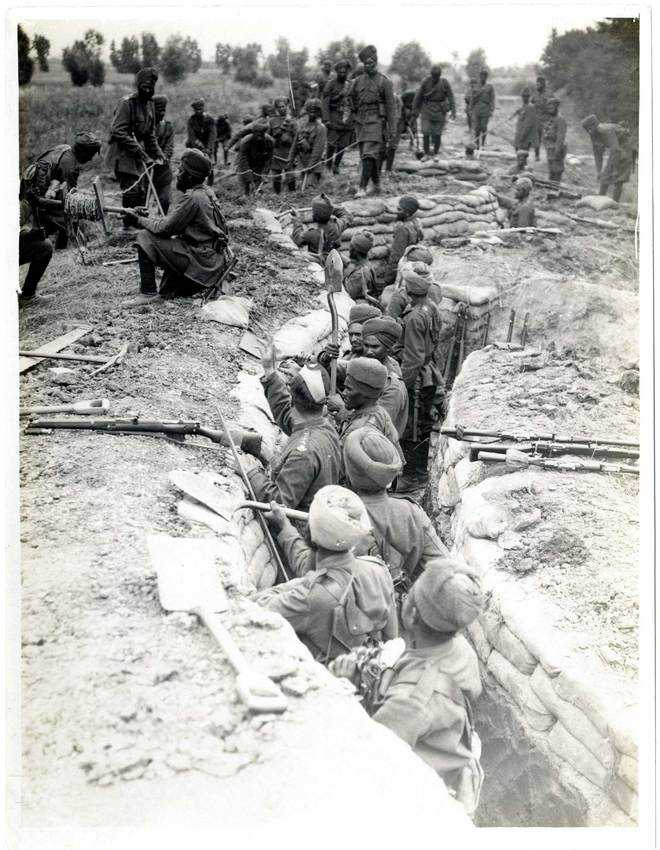

Anxious soldiers digging the trenches in Fauquissart, France

The seaside palace at Brighton turned into 689-bed hospital for Indian troops

Indians receiving electrical and galvanic treatment at the Kitchener Hospital

For all those who have followed World War I centenary commemorations for the last four years, these images have become a part of the memory. All thanks to one man, HD Girdwood, who started photographing the Indian troops in the battlefield and off it.

Girdwood was born in the era of stereoviews. After graduation, he moved to London from his birthplace in Ontario, Canada, and started working as a salesperson with a stereoview company named Underwood. He quickly moved up the ladder. Historian Ralph Reiley says he soon became an accomplished stereo photographer and photographed the Delhi Durbar — a major event of the British government — in 1903 and 1911. In between, he formed his own company, Realistic Travels, in 1908. These travels with the British royalty meant he spent a number of years in India. When the war began, Girdwood realised it was once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and expressed his interest in covering it, especially the Indian troops. He wished for an official position, which did not come his way. Undeterred, he pursued the War Office in London in September 1914 and, in April 1915, managed to get permission, which came with riders. Girdwood could only film and photograph the hospitals in England and these should be reflective of “the great care” being given to Indian soldiers.

Interestingly, this was a time of political awakening in India. Historian Nicholas Hiley has written that the Ghadar movement had begun to show its impact around the time and the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the British Army wanted to show patriotic films showing Indian troops in the field. The War Office was worried. Around this time, Girdwood had also renewed his efforts to go further closer to the scene of action. He was finally allowed a 14-day trip to France with the Indian Corps. Reiley says he was told not to photograph distressing pictures of wounded men. In four days, he covered 70 different locations. While Girdwood had problems with the War Office, he soon persuaded the India office to help him grant permission to click the way he wanted. Rules were relaxed and Girdwood's subsequent photos are from the second or third line trenches. As Ghadar influence intensified and Indians began to believe that Indian troops were the ones in the front lines, the War Office felt the need to propagate that British were facing the brunt as much. So battle scenes were now staged for Girdwood with British soldiers wearing German soldiers’ uniforms. By the end of the war, he had a lot of photographs and a film, With the Empire’s Fighters. Reiley says Girdwood wrote a series of articles for Windsor magazine. The war propaganda had some factual and mostly fabricated stories, which he wrote with his photographs from 1915. He died in Michigan in 1964.

Reiley says First World War stereoviews by Realistic Travels were of the highest quality. “They were the sharpest and the clearest.” He also says that as we look at the stereoviews, we also must remember that they were a medium of entertainment rather than a medium for journalistic truth.

The Indian connect

His family remembers Girdwood as “a shrewd salesman who seemed to chase money where he could find it.” John Girdwood, to whom Girdwood was paternal great-grandfather's half-brother, says he seems to have found some military officers in England (where he lived, worked, and sold for a time). “Those officials probably provisioned some work from him, causing him to go to India. I believe that around 1900-1905, he was a young salesman, eager to make money. That must have prompted him to go to India.” According to historian Ralph Reiley, it is also believed that he served as a Bombay mayor at some point of time. If that were to be the case, his photographic exploits in the area would be worth seeing.