The Irish matriarch of Punjabi theatre

Sakoon Singh

In these times when the discourse has turned highly monolithic, it serves us to highlight the importance of hybrid spaces. And that is what makes it important for us to tell the story of this great Irish dame.

Norah Richards’ tryst with Punjabi theatre began in 1908 when her husband, Philip Earnest Richards, accepted a job as Professor of English Literature at Dyal Singh College in Lahore. Having been a professional theatre actor back home in Ireland, she was naturally curious towards the form in India, but was disappointed to see that despite Lahore being the epicentre of cultural life of Punjab, vitality in theatre was sorely missing. The horizon of folk theatre had remained limited while urban theatre was more or less an insipid, unoriginal affair and the reasons were not very farfetched.

The Macaulay’s Minute-driven education system showcased British literature as a high point of civilisation, primarily for an unequivocal assertion of cultural superiority. In hindsight, it is common knowledge that the introduction of curriculum of English studies at this point in India was complicit with the idea of the Empire.

Gauri Vishwanathan, in Masks of Conquests (1989), exposes the motive behind the introduction of Shakespeare in Indian classrooms and the elaborate effort involved in anointing him as a ‘superlative’ dramatist of all times. So combined with a general Punjabi apathy to arts, the overwhelming influence of English education was responsible for this sordid state of affairs.

It is in these circumstances and ideological moorings that one has to situate Norah Richard’s contribution. She had an early association with the Theosophical Movement, Annie Besant and Home Rule League and the Irish Renaissance. In Ireland, there was a surge of pride gendered by the Gaelic revival, by the retelling of ancient legends and books such as the History of Ireland by Standish O’Grady and A Literary History of Ireland by Douglas Hyde. Around these decades, poet WB Yeats and Lady Gregory were setting up and running the nationalist Abbey Theatre which showcased writings of Yeats as well as Synge. These influences were behind her assiduousness in pushing for more original writings and an indigenous theatre movement in Punjab.

Folk theatre spurred by figures like bhands and mirasis had flourished in Punjab as an unbroken tradition for a millennia. However, the sporadic stage productions were lifting scripts wholesale from West and producing pale imitations of Western dramas that were mimetic to the extent of being ludicrous. Her contribution to Punjabi theatre started at this point when she exhorted young college students to start with producing original one-act scripts in Punjabi. In these years, she directed a few important productions on social issues with a reformatory zeal. Since there was a dearth of modern scripts in Punjabi and the earlier ones were getting somewhat archaic for the very dynamic experiences unfolding in the social and political, this step was the need of the hour. In the following years, she organised competitions for drama writing. Dulhan (1914) by her pupil Ishwar Chandra Nanda became the first full-length modern Punjabi play. She had duly set a process into motion.

Upon the death of her husband in 1920 and her return to India after a tumultuous visit to Ireland, she settled in Andretta in 1924, a small hamlet in Kangra Valley and bought an estate called Woodlands from an Englishman who was departing to England. On this 15-acre plot, she got a rustic mud house with thatched roof constructed; she named it Chameli Niwas. With the support of trusted aides like Prof Jai Dayal, a school of drama flourished from these precincts.

Inspired by her, theatre artistes like Dr Harcharan Singh and Gurcharan Singh, painter Sobha Singh and BC Sanyal, who went on to become India’s foremost modernist painter, became her neighbours. She became totally engrossed in carrying out her work on theatre and every year, in March, she organised a week-long festival in which students and villagers enacted plays in the open-air theatre on her estate. Prithviraj Kapoor and Balraj Sahni were regulars at this annual pilgrimage and Balwant Gargi wrote some plays here. The small settlement became a nursery of sorts for myriad art forms.

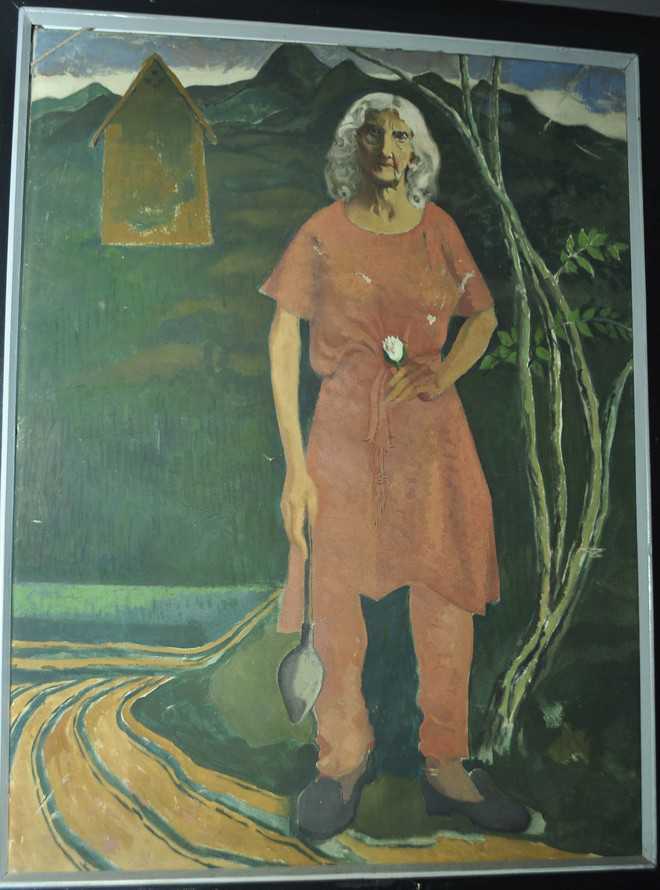

Owing to her unusual work patterns, the house became the repository of many legends. She was said to maintain strict discipline at the estate and her day that involved gardening and writing was clockwork. She would be seen in a khadi dress bending over plants with a khurpa and sun hat. She became increasingly eccentric and punctilious. The plays that she scripted and directed were reflective of the social issues in Punjab and it is documented in several letters that she was really disturbed by, among other things, the bloodshed that accompanied the Partition.

Norah Richards has come to be called the “Lady Gregory of Punjabi Theatre”. It is another matter though that people neither know about Richards nor about Lady Gregory and the reasons are not too difficult to figure out: these references are distant and it is in Punjab’s own apathy to the arts as a whole. It is the same tendency that Norah purportedly tried to fight in her own time.

In these fraught times when issues of identity have become highly polarised, a reassessment of Norah’s contribution to Punjabi theatre goes on to show her strident passion for aesthetic freedom and her espousal of these core values for spurring a growth of theatre in Punjab. If one were to sum up her contribution, it lies in her ability despite being an outside figure, in nudging people towards an honest engagement with their own arts. If one were to join the dots, for her it all started as a young actress in Ireland, where people, too, were endeavouring to embrace their Gaelic antecedents and shaking off the shackles of British influence in similar ways.

At times, it takes an objective, outside view to bring some truths home.