The end of madness

Sarika Sharma

Indian tribal artist commits suicide in Japan.

The news didn’t create ripples. A handful of progressive painters protested vehemently. Nothing moved. Neither the Japanese museum nor the Japanese government felt accountable enough to send the body back. No one was bothered. No matter the dead tribal was a celebrated painter, or that Europe was crazy about him. No matter he made tribal art fashionable…

In all these years, there has always been one easy explanation to Jangarh Singh Shyam’s death: ‘Depression’. Fine. But what drove him to that? In his book, Invisible Webs, filmmaker Amit Dutta chronicles Jangarh’s life and the causes that could have led to his death, 10,000 km away at a museum that was meant to celebrate his art.

The book is a result of Dutta’s fellowship project at the Indian Institute of Advance Study in Shimla. As he set out to enquire into Jangarh’s death, mapping his life through conversations with the people who knew Jangarh, he realised that the reason for the suicide was not to be found in present-day Patangarh or Bhopal. It was to be discovered in the chasm that separates ‘them’ from ‘us’.

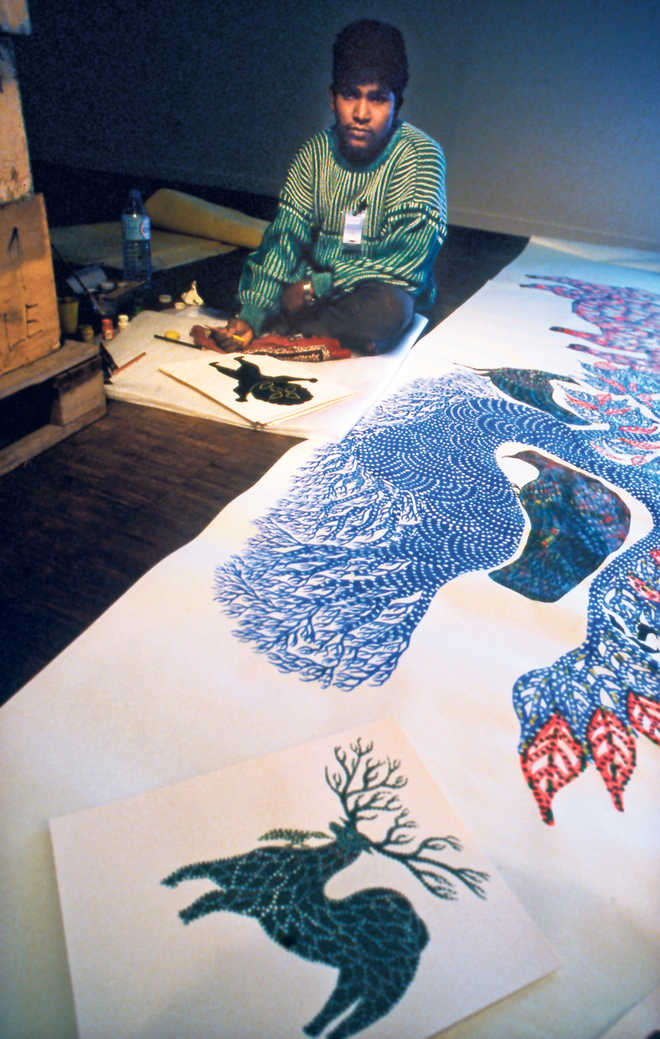

Jangarh gave shape to the earlier formless Gond deities, but his designs were tethered to the walls of the houses in Patangarh village in Bhopal, better known as home to British anthropologist Verrier Elwin. Jangarh was spotted by talent scouts from Bharat Bhavan and he came in contact with its director, artist J Swaminathan.

He left the village for the city, which the tribals call a “merciless world”. He fell in love with the synthetic colours when he first touched them. It sent shivers down his spine. Dutta writes there was no precedent in the village of the colourful paintings Jangarh made. Bright colours were one of the major reasons why he moved to the city and bright colours were to remain his enduring passion.

Dutta counts the influences that the city had on him. He was improving his technique, gaining more control over his medium, was able to avoid splodges and get a thinner line, etc. But he did not want to imbibe ‘city art’. He knew what he wanted from the city: The point of going to the city is not to change your art, but to sell it, he would say. He was 17 when his art was first displayed along with that of eminent painters.

Dutta says Jangarh showed a remarkable sense of self-respect regarding his poverty and refused to idolise anyone as his mentor. “Identifying himself with the poor and exploited... with a deep distrust for the corrupt bureaucratic government and its schemes of which he had had direct bad experience, convinced about the unaccountability of the government or the state towards him and his people, he rather held on to his village community as his only insurance.” He invited them to Bhopal, encouraged them to develop their own individual style and would distribute a considerable share of his earnings among his villagers.

Hailing from a small town in Jammu, Dutta’s own exposure to the outside world was limited. In that, he sees a parallel between his and Jangarh’s life. Dutta happened to get educated at the FTII and carve out his own path. He is today an award-winning experimental filmmaker, best known outside India, little known in India, where they like to call him “a recluse”. So what failed Jangarh? Dutta would like our institutes to bear some responsibility.

Talking about how it was presumed that India was ready to be modernised on the lines of the western model of industrial infrastructure, he says institutions of education and culture followed a similar approach. Dutta says our modern, liberal institutions for the arts “might be more international in language, location and culture than national”, but wonders if this is a matter of pride or concern? And he remembers what Swaminathan once said about working in the jungles of Madhya Pradesh: ‘No place in the state is far away; it is only we who are far away from the places and the people.’

Dutta sees Jangarh’s migration to Bhopal as time travel, from primitive to contemporary. He says that with our public institutions, we have forged a common language across the globe, but not with the tribal or villager who might live just a few kilometers away. And he questions our priorities, which make a Jangarh world famous but little known in his own home.

So, while Jangarh brought tribal art to the mainstream — and now beautifies T-shirts and coffee mugs for tourists, canvases of artists in the villages await buyers. Our institutions and metropolises, our temples of progress, have failed in their promise to accommodate them. Dutta says that if institutes like NID and FTII stop giving back to the people their due, they will stop receiving anything from society too, merely because society would have nothing left to give, neither wisdom nor tradition, nor even the will and wish for wisdom and tradition.

Dutta says Swaminathan, Jyotindra Jain and Gulam Mohammed Sheikh did their best to publicise Jangarh’s art, but the distance between the city and his roots could never really be bridged. He made tribal art famous, brought it into the mainstream, but the mainstream that romanticises the primitive never really came close to him.

During his ill-fated trip to Japan (he had liked the brief first trip and named his daughter Japani after the place), Jangarh was being pressurised to paint more than he felt inspired to. His passport was withheld. His stay was extended. Not knowing any language to communicate in that alien land, he was left to fend for himself. He repeatedly wrote to his wife in Gondi and begged her to arrange for his return and finally “killed himself in the Living Museum of Asia in the land of the glorified hara-kiri”. The museum owner refused to send the body back for he ‘had not budgeted for the contingency’. The common man was informed of the death through “few” obituaries. “The epic tragedy became a news story, and faded away with new editions of more urgent news.” Jangarh had died at 39.

At Patangarh, Dutta meets his nephew, who wants to paint and sell his art in the city. Day after day, Patangarh artists still head to the city, following in Jangarh’s footsteps. What will their fate be?