Gurez, an ‘offbeat’ paradise

Manisha Gangahar

Through the window of her Kashmiri ‘living room’, Kaneez Fatima points at a pristine white broad peak —“That’s the HarMukh,” she announces, as she pours the traditional kahwa from her samovar. In her Kashmiri-accented Hindi, she adds, “HarMukh is believed to be the abode of Lord Shiva. It is an important reference in Kashmiri Hindu mythology.” Geographically, it is located between Nallah Sindh in the south and the Kishanganga river in the north.

“Many from Gurez, particularly the ones who could afford to, have moved here in Bandipore due to extremely harsh life conditions there, but they remain distinct,” says Fatima. Remote and pushed into oblivion, Gurez was once a significant milestone on the erstwhile Silk Route. The Partition divided this ancient Dard-Shina civilisation geographically, and even their hearts with families and kin pushed to either side of the LoC. “As you drive into Gurez, do stop to talk to the Shina-speaking Dards, each will have a story to tell,” she suggests.

The journey into the Greater Himalayas speaks for itself — enchanting and fulfilling. The preface has been gratifying — Wular, Asia’s largest fresh water lake, as you look down from the roadside, and tilt the head upwards, the HarMukh gleams back. It is up till Tragbal that a few dhabas, offering chot and lavaas with nun chai, could also be seen. The snow-capped Himalayan mountains make their appearance as we cut across the Razdan Pass at 11,672 ft.

Cool breeze flutter rows of green flags at the shrine of Peer Baba, which is under Army’s patronage. “The practice began way back in 1947, I think,” says Harpreet Singh of Patiala. In the year since he has been posted here, he has heard many stories: “Soldiers believe that they return from the dangerous LoC because of the blessings of Peer Baba, who had come to Razdan in 1940, after roaming without water and food for months.”

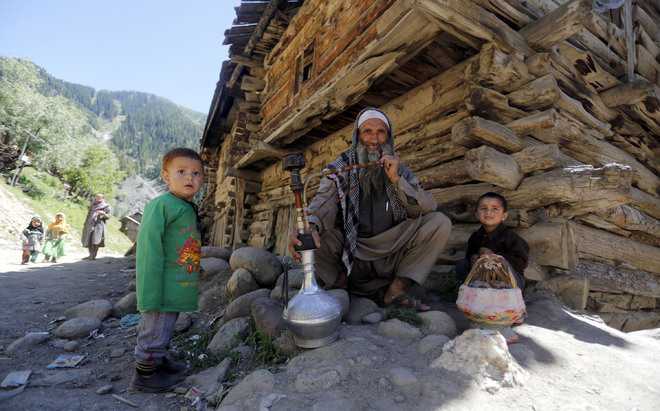

A brief halt further only to digitally capture the view leads to a chance encounter with Hussain, an elderly Bakerwal, who has spent the 60-year stint crossing the Razdan every year. His radiant smile makes up for his awry expression. Does he understand what it means to have a home? He is quick to share his wisdom passed through generations, “We are at home among the mountains, we know the paths like nobody else, and ours is a different world altogether.”

Bakerwals, tells us an Army jawan posted at Razdan, are important as informers but he had another story to add: “Once I approached Khan Baba for a cure to my fractured forearm, and he made it as good as it was earlier. They seem to know all about local herbs.” Before bidding a goodbye, Hussain tells us that this Razdan pass, or the Bandipore-Gurez highway road is a notorious one: “Khatarnaak stretch, especially when wet and in dark. A diversion goes to Chilas, in Pakistan, and the route was used for trekkers for K2 summit.”

As we roll down the Razdan, breathtaking views keep panning out. Now at Kunzalwan, it is man versus nature, and who tames whom is just a matter of time. The Kishanganga power project here has changed the landscape. Touching Dawer, the headquarters of Gurez, is stepping into another world: mountains rising high on all sides, water compellingly flowing, creating its own melody, wooden log houses amid green meadows. The only flip side being the six-hour power facility. “That is good enough. What more would you need it for anyway,” proclaims Haji Ghulam Muhammad Lone, the caretaker at TRC huts in Dawer.

Haji Chacha, as everybody calls him, has spent his entire life in Gurez. At 70 now, he is a contented man: “It is beautiful here. Nothing can match the feel of this place.” He arranges for a little evening picnic next to the waters of Kishanganga with Habba Khatoon, a pyramid-shaped limestone rock, rising tall and magnificent, overlooking Dawer, behind us. “It is not just a colossal stone, but with it the memory of Habba Khatoon, wife of Kashmiri king Yusuf Shah Chak, is permanently engraved in the minds of the people of Gurez,” he says. A woman, poetess, queen and a beloved, who is believed to have been wandering in the valley, in search of her lover, Habba Khatoon is the essence of Kashmiri thought process.

Driving beyond Dawer takes us further into the rustic Gurez. Passing through Burnai, Sheikhpura and Jignia villages, halting several times to make an entry at the Army posts, we gather some more undocumented chronicles.

The astounding expanse of the mountains makes up for the bumpy road but the apotheosis of the journey is the conversation with Abdul Rahim Lone, at his home in Chakwali, the last village on this of the LoC. “Strange faces are always welcomed, for we hardly get to see humanity,” he tells us, narrating the tough lifestyle due to the remoteness of his place. Belonging to the Dard-Shini tribe, he laments the loss of ties and contacts with those in Gilgit: “My father and grandfather used to go visiting but we have lost our connections. As a child we used to wait for those special khurmanis that grandfather brought from Gilgit.”

His wife, Sajda, is more sombre. “Women have even harder life here, but it is alright,” is all that she shares but treats us to a folk song in now-getting-extinct Shina language of the Dards. Mesmerising! The water stream just behind the house, fir trees queuing up and the mountains surging in the background, hours would pass by sitting still at the log home window, with boundaries of all kinds blurring away.

Quick facts

- The Gurez valley is 123 km from Srinagar.

- No permit is required but identity proof needs to be shown at Army checkposts.

- The drive till Dawer is 6-7 hours.

- The road is unpaved, except for the stretch at Razdan Pass.

- There are a private guesthouses and motels in Dawer, the headquarters of Gurez.

- Electricity supply is limited from 7 pm to 11 pm and 4 am to 6 am per day.

- The market at Dawer offers all basic necessities. The days are warm and nights cool, during summer months.

- Jio and BSNL are the only network providers — that too, till Dawer.