Give farmers a fair deal

Soon after the Economic Survey-2016 brought to light that the average farm income in 17 states — roughly half of India — was less than Rs 20,000 a year, a newspaper reported the squabble between officers of the Supreme Court and the defence services over washing allowance which they get as part of their income package. The defence service employees were reportedly questioning why the officers of the apex court were getting a higher washing allowance of Rs 21,000, while their own entitlement was Rs 20,000. It made me wonder: Don’t farmers have clothes to wash?

The average income of a farm family in half the country equals just one of the 108 allowances (in total, for all the services put together) that the government employees get as part of the 7th Pay Commission. A perusal of the NSSO (National Sample Survey Office) data that the Economic Survey-2016 had quoted shows how glaring is the income divide. The NSSO had deviated from the usual practice of computing farm income on the basis of what the farmer sold in the market to — for the first time — work out farm income on the basis of marketable surplus a farmer sold in the mandi and adding to it what he saved for his family consumption, which means it is the average of the total value of farm output in roughly half the country.

Shocking details of almost non-existent farm income that the Economic Survey-2016 provided failed to evoke outrage. Perhaps it was because Prime Minister Narendra Modi had at the same time promised to double farmers’ income by 2022, thereby overshadowing the reality. Income inequality is woven into the predominantly market-driven economic structure. This is substantiated by the latest agricultural growth estimates of the Central Statistics Office, showing the nominal gross value added (GVA) in agriculture in October-December 2018 to have dropped to its lowest in 14 years, clearly showing how farm income has plummeted. But it failed to shake the nation’s conscience. The plight and systematic decimation of agriculture over the years has for all practical purposes been taken for granted.

Staggering losses

A study by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in collaboration with the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) has computed the total loss farmers have suffered between 2000-01 and 2016-17 — by being denied the rightful price for their produce — at a staggering Rs 45-lakh crore. As per the findings of the Niti Aayog, it is estimated that real farm income increased by just 0.44 per cent every year between 2011-12 and 2015-16. It further admitted that the near-zero income of farmers in the past two years (after 2016) has forced the government to launch a direct income support scheme (PM-Kisan), which makes a provision for directly transferring Rs 6,000 every year into the bank accounts of small farmers.

With agriculture in such a dismal state, it is futile to expect the non-farm sector to be performing well. A latest study shows that rural non-farm wages in the past five years, too, have dipped to their lowest. A CMIE (Centre for Monitoring of Indian Economy) study stated that of the 56.6 lakh job losses in the past 12 months, almost 82 per cent are from rural areas. Rural India had somehow survived the unprecedented distress conditions, and this is nothing short of a miracle. Any other business with such huge losses would have collapsed by now, and even disappeared from the economic horizon.

Agriculture remained at the receiving end not only in the past 20 years, but also prior to that. According to an UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) study, global farm gate prices, when adjusted for inflation, had remained almost static between 1985 and 2005. Farm income has remained frozen for almost four decades. “To be born in debt, and live all through in debt, is like virtually living in hell,” remarked Declercq Gilbert, a 93-year-old farmer in Leshonnelles village, about 15 km from Mons near Brussels, when I met him last year.

Indian agriculture, too, had slogged with farm income remaining almost frozen. In 1970, the minimum support price (MSP) for wheat was Rs 76 per quintal. In 2015, it was Rs 1,450 per quintal, an increase of 19 times. For the same period, I examined the increase in basic salary plus DA (not adding other allowances) for different sections of employees. For government employees, the increase was 120 to 150 times; for college/university lecturer/professors, it was 150 to 170 times; for schoolteachers, it was 280 to 320 times. If only the wheat MSP was raised in the same proportion, which means if it had gone up let’s say 100 times in the 45-year period, farmers should have received at least Rs 7,600 per quintal. What they actually got was an MSP of Rs 1,450 per quintal in 2015. In other words, it is the farmers who are bearing the cost of subsidising the consumers. The burden of keeping food prices low has been conveniently passed on to the farmers.

Glaring shortfall

Farmers dumping tomatoes, potatoes and onions on the roads is a recurring phenomenon. In recent years, news reports have highlighted that farmers are being denied the appropriate price in the mandis, the drop in prices often ranging from 25 to 40 per cent. Using the latest CACP (Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices) cost of production statistics for rabi and kharif seasons and comparing this with the average income per crop as worked out by the Dalwai Committee on doubling farmers’ income, Down to Earth magazine (February 16-28, 2019) has presented a damning analysis. Against the production cost of Rs 32,644 per hectare for wheat, the income realised by the farmer is Rs 7,639, leaving a shortfall of Rs 25,005 per hectare. In the case of paddy, the gap is Rs 36,410 per hectare; for maize, the loss a farmer incurs per hectare is Rs 33,686; and for arhar it is Rs 26,480 per hectare.

Although only 6 per cent farmers, as per the Shanta Kumar Committee, get the benefit of MSP, the fact remains that the announcement of MSP neither helps in setting a floor price nor does it guarantee an assured price for farmers. This is primarily because the mandate for the CACP, which works out the MSP for various crops, is not only to provide an assured price to farmers but also to ensure that it does not lead to inflationary pressures. The macro-economic policy has a lot to do with the prevailing farm crisis. The prices have been kept low, and in most cases actually less than even the cost of production.

The MSP the government announces actually includes out-of-pocket expenses incurred by farmers in crop cultivation (A2 cost) plus the cost of hiring farm labour (FL), including family labour, a farmer employs. In addition to this cost, which is labelled as A2+FL, the government claims that the MSP being announced since the beginning of the kharif season last year contains 50 per cent profit. Although the government asserts that it has honoured the recommendation of the Swaminathan Commission, which had suggested 50 per cent profit over the comprehensive cost, the new formula falls short of what was in reality recommended. Nor has the government been able to ensure that procurement is made at the MSP it has announced. Several farmer leaders have questioned the government’s claims, and the trade data showing the shortfall in prices paid to farmers in various mandis is routinely shared on social media.

It is the methodology of working out the cost of production that has somehow gone unquestioned. Although an elaborate system exists for collating statistics pertaining to the cost of production, crop-cutting experiments to work out the production achieved and so on, the costing falls acutely short of the way the prices of agri business/industrial goods are worked out. While the employees get 108 allowances in addition to basic pay plus DA, and the cost of processed food includes administrative cost, and marketing cost plus profit as it may deem fit, when was the last time we heard of farmers getting at least four allowances — house rent allowance, travel allowance, health allowance and educational allowance for their children included in the final price? And why not? A farmer also has to look after his family. Worked out on per-hectare basis, these allowances can be easily included in the MSP calculations or paid directly into their bank accounts.

Social implications

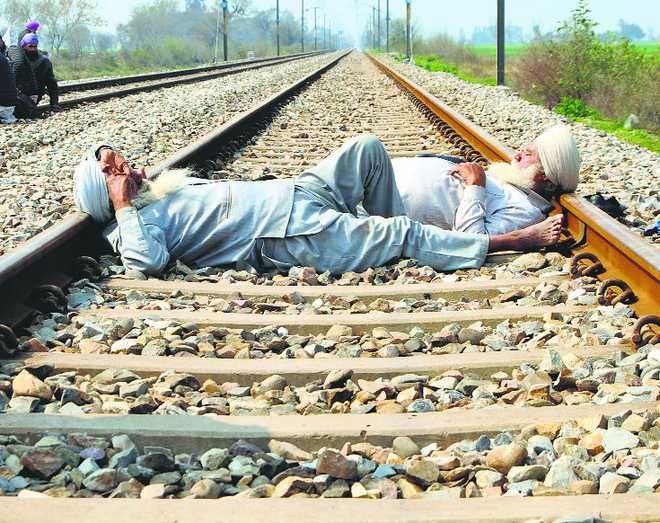

Denying farmers their rightful income comes at a heavy social cost, which often gets clubbed under mounting indebtedness. As per the National Crime Records Bureau, between 1995 and 2015, 3,18,528 farmers committed suicide. The debt burden is the primary reason for the serial dance of death that continues with impunity.

All this adds to visible disruptions in the social fabric. “No girl wants to marry a farmer. Young farmers are leaving farming and going to Pune and Mumbai to work as taxi and rickshaw drivers. They say that if not money, they will at least get a bride in the city,” Mohan Patil from Satara (Maharashtra) told a newspaper. This is true of Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and many other states. Even in the prosperous apple belt of Himachal Pradesh, not many girls are willing to settle down in the villages. Low income levels and harsh working conditions are cited as the main reasons for girls unwilling to settle in rural areas. It’s not only in India that young farmers find it difficult to get a bride; it is not so easy even in Europe, Canada, Australia and the US.

As the policy emphasis remained essentially on increasing crop productivity, primarily to ensure that the availability of food was at a comfortable level, farm income never received the kind of thrust it deserved. Agriculture had been deliberately kept impoverished to keep economic reforms alive.

In 1996, the World Bank had wanted India to move 400 million people from rural to urban areas in the next 20 years, by 2015. These are ‘agricultural refugees’ swarming the cities in search of menial jobs. It is primarily for this reason that over the years, in addition to more or less static farm income, public sector investments in agriculture were also kept deplorably low, hovering between 0.3 and 0.5 per cent of the GDP during 2011-17. The total investments, both public and private, have also been declining steadily — from 3.1 per cent of the GDP in 2011-12 to 2.2 per cent in 2016-17. Compare this with the tax concessions being given to the industry, which accounts for 5 per cent of the GDP.

Former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan said the biggest reforms would be when we are able to move people out of agriculture, to migrate to cities which need cheap labour. Even the new Chief Economic Adviser has called for more investments in the industry so as to pull the youth from agriculture. If agriculture has to be treated as a source of cheap labour in the cities, it speaks of the flawed economic thinking that has led successive governments to dismantle the strong foundations that sustained millions of rural livelihoods.

Strengthen public procurement system

- At a time when MSP benefits only 6 per cent of the farmers and the rest are in any case dependent on exploitative markets, the focus has to be on strengthening the public procurement system. Besides making MSP more realistic, covering all aspects of cost calculations, the emphasis has also to be on ensuring that whatever surplus the farmers bring to the markets is purchased at the official price announced. Although the government did announce assured procurement under PM-AASHA (Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyan), it failed to ensure its implementation.

- There are two problems the government is encountering. First, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) is keeping a close watch on the increase in MSP, classified as farm subsidies in international trade parlance. The US, EU, Canada, South Africa, Pakistan and others have repeatedly questioned MSP on wheat, rice and pulses, saying that the prices have breached the permissible de minimis support limit allowed to developing countries. India is expected to keep MSP within the prescribed 10 per cent limit of the total value of a particular crop. This acts as a strong deterrent to raise MSP as per the farmers’ demand and not face the WTO’s ire.

- Not only WTO, there is strong lobby within the country that advocates dismantling the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandis so as to enable farmers to realise price discovery. The underlying objective is to allow private terminals to take over instead, laying the foundation for corporate farming. Already several states have suitably amended the APMC Act, removing fruits, vegetables and livestock products from the mandi operations. But this has neither helped farmers realise a better price for their produce nor reduced the arrival of fruits and vegetables into the regulated markets. Bihar had revoked the APMC Act in 2006 with the objective of attracting private sector investments in market operations. Nothing like this happened, and even now truckloads of paddy and wheat are routinely brought and sold illegally in Punjab and Haryana mandis.

- Instead of dismantling APMC mandis, the policy emphasis should be on expanding the existing network of mandis. There are nearly 7,600 APMC markets operating at present and if one mandi has to be provided in 5-km radius, India will need 42,000 mandis. Public sector investment must be directed towards strengthening the mandi network. If India can provide Rs 6.9 lakh crore for building highways, why can’t at least Rs 1-lakh crore out of it be diverted for public sector agricultural market infrastructure?

- Unless there exists adequate market infrastructure, no meaningful reforms are possible in agriculture. While it is generally agreed that APMC mandis have become a den of corruption with strong cartels of middlemen operating, the answer does not lie in throwing the baby with the bathwater. The APMC is crying for a change, and the introduction of electronic operations (in eNAM markets) has certainly helped. But a lot more needs to be done if genuine improvement is required. Merely replacing the public sector with private companies will defeat the purpose. Nowhere in the world, and that includes the US/EU, have the private markets helped farmers with a better price. Even the value chains have failed to prop up farm income.

Policy impetus a must

- Moving from ‘price policy’ to ‘income policy’, the government has brought in a breath of fresh air into public policy. While doubling farm income by 2022 remains more or less a slogan, Telangana’s ‘Rythu Bandhu Pthakam’ scheme, under which farmers were initially paid Rs 8,000 per year per acre (with no upper cap), followed by KALIA (Krushak Assistance for Livelihood and Income Augmentation) scheme launched by Odisha, and since then some variants brought in by Jharkhand, West Bengal, Karnataka and more recently in Andhra Pradesh have heralded a direct income support programme for small and marginal farmers.

- The Centre has chipped in with the PM-Kisan programme, which entails providing Rs 6,000 per year, in three instalments, to small farmers with landholding less than 2 hectares. While the first instalment of Rs 2,000 has already been paid to a large number of farmers, the government said it would need an additional Rs 75,000 crore every year to fund this scheme.

- Whether it is because of political compulsions or driven by the dire need to augment farmers’ income, the introduction of a direct incom