The real idea of swaraj

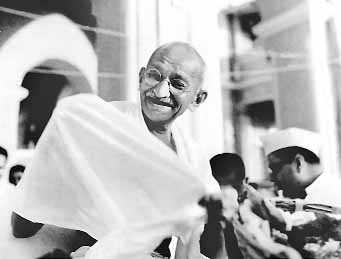

ON the day of India’s Independence in August 1947, Mahatma Gandhi refused to join the nationwide festivities and remained in the riot-torn district of Noakhali in East Bengal to restore peace between Hindus and Muslims. That dark shadow of despair still haunts every time we think we need to celebrate our ‘independence’. It was characteristic of Gandhi that he questioned the authenticity of independence in the aftermath of the Partition violence. But more importantly, he began to feel that colonisation had made deep inroads into the Indian mind and needed to be undone urgently.

He had written Hind Swaraj in 1909 as his manifesto for ideological independence when the attainment of swaraj was the immediate task facing colonial India. Gandhi draws a subtle distinction between swaraj as self-rule and swaraj as self-government or home rule. Swaraj as self-rule is the rule of the self by the self or more precisely, the rule of the mind over itself and its passions. As swaraj is something that is capable of being experienced within oneself, the inner experience of self-rule enables the citizens to reinforce their political ethics by their conduct, in harmony with their native genius.

Gandhi was suspicious of the modern West primarily because of its obsessively materialistic world view. To him a culture, which did not have a theory of transcendence, could not be morally or cognitively acceptable. The legitimation of the modern West as a superior culture came from an ideology, which viewed oriental societies as inferior to the occidental ones. With the acceptance of this ideology, the superiority of the West became an objective criterion of evaluation of other cultures. Even a liberal like JS Mill endorsed this civilisational partition of the world and used the very doctrine of liberty to justify the imperial rule over the world.

Gandhi felt that it was necessary to revitalise tradition to protect autonomy of the individual. Living through the era of British imperialism, and when the most insidious effects of colonialism were showing in India, he was anxious to teach the Indians that ‘modern civilisation’ posed a greater threat to them than did colonialism and that in any case colonialism itself was a product of modern civilisation. At the heart of Western modernity is the faith that reason alone will lead inevitably to a progressively better future. Gandhi held that the great weakness of modern civilisation was its failure to understand the nature and limits of reason. In his view modernity displaces other modes of thinking and moral points of reference, such as those found in religion and tradition which speak to the moral and cooperative nature of man and challenges the self-interests that are lodged in a person and in a society. Tradition was a resource, a source of valuable insights into the human condition, and part of a common human heritage. He therefore became a resolute critic of modernity.

Gandhi valorises traditional India for as much as it was able to maintain a certain openness of cultural boundaries, a permeability that allows new influences to flow in and be integrated as a new set of age-old traditions. These two processes of inflow and outflow, rather than a rigidly defined set of practices, determine Indian culture at a given point of time. Since Gandhi’s Hinduism reaffirmed the non-canonical and the folk, his was a defence not of a religion or theology but of an open-ended way of life on the assumption that, with such a base, Indians would cope better with modernity. His distrust of modernity has found echoes among many political and environmental movements around the world.

To be sure, there is nothing wrong in embracing elements of another culture, no matter how different it is from one’s own. The point is that neither Western modernity nor indigenous tradition must be blindly accepted or rejected. Gandhi, one of the most original minds of the 20th century, did not want his house to be ‘walled in on all sides and his windows to be stuffed’. He wanted the culture of all lands to be blown about his house as freely as possible but refused ‘to be blown off’ his feet by any.

In October 1931 the philosopher KC Bhattacharya delivered a lecture called ‘Swaraj in Ideas’, which echoed Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj and warned against ‘the so-called universalism of reason or religion’ which, being the result of a rootless education, stood more than anything else in the way of ‘swaraj in ideas’. He talks about ‘cultural subjection’ vitiating the very springs of our intellectual and moral life, which persists even today. According to Bhattacharya, ‘there is cultural subjection only when one’s traditional cast of ideas and sentiments is superseded without comparison or competition by a new cast representing an alien culture which possesses one like a ghost’. His lecture exhorts Indians to shake themselves free from it.

Bhattacharya concludes his lecture thus, ‘we condemn the caste system of our country, but we ignore the fact that we who have received Western education constitute a caste more exclusive and intolerant than any of the traditional castes. Let us resolutely break down the barriers of this new caste, let us come back to the cultural stratum of the real Indian people and evolve a culture along with them suited to the time and to our native genius. That would be to achieve swaraj in ideas’. How the words ring true after seven decades of our Independence!

— The writer is a former Fellow of the IIAS, Shimla