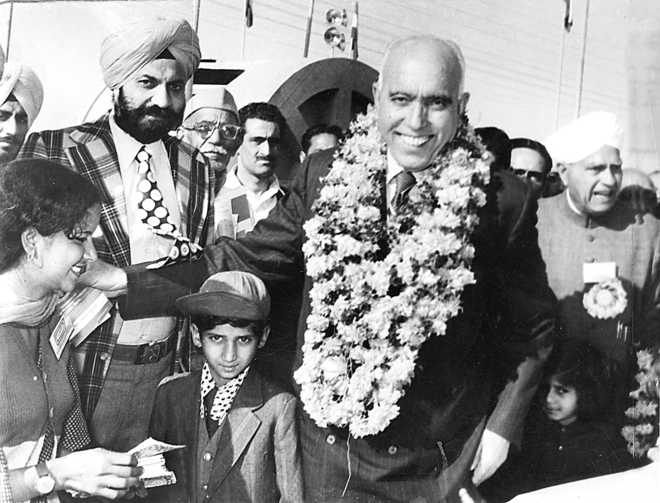

Revisiting Sheikh Abdullah’s arrest in 1953

Vappala Balachandran

Ex-Special Secretary, Cabinet Secretariat

Doubt exists even today whether Sheikh Abdullah was arrested in 1953 on a faulty reading of the mind and motives of that complex personality. Some say that he was a closet sympathiser of Pakistan, while others affirm that he was totally aligned to secular India. Some believe that he was pursuing the independence option, like his bete noire Hari Singh. There are others, like former Foreign Secretary Yezdezard Dinshaw Gundevia, who believe that he was arrested after a typecast police investigation. Gundevia was then handling Kashmir in our foreign office as Joint Secretary.

BN Mullik, then Director, Intelligence Bureau, who had prepared grounds for Abdullah’s arrest, says that the first rupture between the Government of India and the Sheikh came in January 1949 when the three-point proposals of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP), especially plebiscite, were being discussed. Abdullah would not agree on plebiscite since the National Conference had passed a resolution in October 1948, favouring accession to India. This impression is not correct as Abdullah had clearly objected to the plebiscite idea in his anti-Pakistan speech at the UN Security Council on February 5, 1948.

Mullik joined the IB only in September 1948 from the Bihar police as Deputy Director. He had no experience on Kashmir. He mentions Abdullah's towering status in Kashmir, but found difficulties in judging the veracity of reports from there on account of deep rivalry between Hari Singh (Jammu) and Abdullah (Valley). His first conflict with Abdullah was in January 1949 when the local IB officer started inquiries about an interview with foreign correspondents Michael Davidson and Ward Price when Abdullah spoke of ‘independence’. Senior minister Gopalaswamy Ayyangar, who was handling Kashmir, advised Mullik to withdraw the IB officer ‘in larger interests’. Ayyangar had to intervene again when Abdullah objected to a new IB officer who was not ‘cleared’ by him.

Mullik could not visit Srinagar earlier than August 1949 to build a rapport with top leaders, although Ayyangar had advised him to meet them regularly. He stayed for 10 days and was convinced that the reports indicating Abdullah's hostile intentions were unfounded. On return to Delhi, he submitted his report to his Director who passed it on to Home Secretary HVR Iyengar. The latter sent copies to Prime Minister Nehru and Home Minister Sardar Patel. Nehru circulated his report to our foreign missions. Patel who was ‘unhappy’ with Mullik's report, summoned him, told him that he did not trust Abdullah and that Nehru should not have circulated it widely. Simultaneously, Patel was also getting reports from Hari Singh about Abdullah's communal agenda.

Mullik, who became IB Director in July 1950, started dealing with Kashmir personally. Things changed in Kashmir at a frenetic pace from the middle of 1949, with Pakistan playing subversive cards, like subverting Pir Maqbool Gilani and NC leader Ghulam Mohiuddin Karra, who formed the pro-Pakistan Political Conference. The IB collected evidence of arms smuggling into the Valley. Abdullah started indulging in competitive communalism. His rhetoric often swung from the independence option to accession to India.

On April 4, 1951, the Yuvraj constituted a Constituent Assembly for Kashmir. Mullik says that it was Gopalaswamy Ayyangar’s idea, but Abdullah used it for his political advantage. Its intention was to ratify accession to India, but its elections enabled Abdullah to emerge as the sole repository of power. This assembly also abolished Maharaja’s rule and created the post of Sardar-e-Riyasat, electing Karan Singh as the first incumbent from November 17, 1952. Mullik says that Abdullah attempted to frustrate attempts by Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, DP Dhar and Sadiq for closer integration with India. Rumours started floating that Abdullah was keeping his options open.

Here, Mullik introduces a surprise twist. He refers to a talk in New Delhi circles that “the Sheikh was the right person to succeed Pandit Nehru or to become his deputy in his lifetime.” Then he refers to an intelligence report that Abdullah was actually a suspected British agent for spearheading the liberation movement in the early 1930s since the British did not like Hari Singh “as he refused to be subservient to him.” “The British had also tried to use this channel to bring about a cleavage between Hindus and Muslims…. I mentioned this to Pandit Nehru and he was surprised.” It is odd that he had introduced an unverifiable factor in his book on Kashmir history published after Nehru’s death.

The final break was the Jammu Praja Parishad agitation in the winter of 1952-53, demanding full integration with India. Abdullah reacted by spewing communal venom against the agitators, which scorched the region. Nehru asked Mullik to proceed to Jammu and deal with the situation. His mission in Jammu was successful. But he was received very coldly by the Sheikh. When he narrated this to Bakshi and Dhar, they asked him to convey to Nehru that “the Sheikh was using this agitation as an excuse to get out of his previous commitments to India.” Abdullah was dismissed by the Sardar-e-Riyasat on August 8, 1953, and arrested.

In his book Flames of the Chinar, Abdullah blames DN Kachru, Nehru's aide, for his rift with Nehru. In 1968, the Shabistan Urdu Digest published Abdullah's long interview. Its English edition was with YD Gundevia’s articles defending Nehru and Sheikh. Abdullah mentioned a 1965 incident while in Mecca when several Muslim countries offered him asylum in the wake of Indian media’s attacks on him. He refused. On his return, he was arrested again.

A few months after Abdullah’s arrest, Mullik met C Rajagopalachari (Rajaji), then Chief Minister of Madras (1952-54) who was Governor-General (1948-50) and had succeeded as Union Home Minister in December 1950 after Patel’s death. Rajaji strongly felt that it was wrong to have arrested the Sheikh. “Rajaji said that the Sheikh should have been given a third alternative of autonomy or even semi-independence and the door should not have been shut against him. He apprehended that continued uncertainty and unrest would prevail in the Valley.”

Should we remember Rajaji’s prognosis when we have now swung the pendulum in favour of Jammu, alienating the Valley?