Minimum working days for MPs, MLAs needed

Partap Singh Bajwa

MP, Rajya Sabha

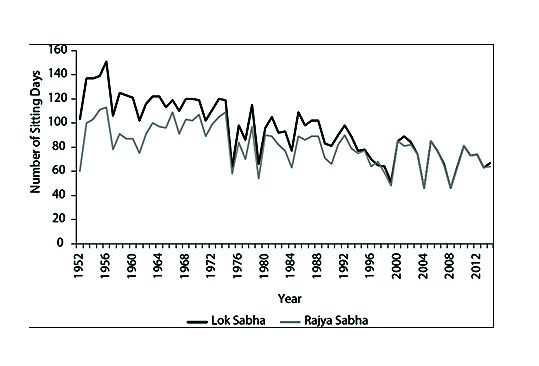

From 1952-1972, the Indian Parliament worked for an average of 120 days each year. In the United Kingdom, our constitutional inspiration, Parliament sits for an average of 150 days each year. In the United States, Congress sits for upwards of 100 days each year. The German Bundestag sits for an average of 105 days each year, and has a pre-set annual calendar. In the last four years, this number for the Indian Parliament is down to just 64 days. Why have we not set the same high standards as our international peers and our own leaders in the past?

The parliamentary calendar is set entirely by the Cabinet. The Constitution's only constraint on this power is that there cannot be more than six months between two sessions. The number of working days, therefore, is entirely a matter of convention. The graph on the left shows the effectiveness of this convention.

The number of working days has consistently fallen. As a result, the time spent on discussing Bills has also reduced. As many as 25 per cent of the Bills in the last Lok Sabha were passed in less than 30 minutes. The entire Union Budget of 2018 was passed in less than 30 minutes.

Undeniably, the blame lies across the spectrum. This government is especially averse to discussion and scrutiny. For instance, in the monsoon session of the Rajya Sabha this year, the government introduced the SC/ST Atrocities Amendment Bill just four days before the end of the session, and theTriple Talaq Bill on the very last day. Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, indeed!

Even increasing disruptions in Parliament are linked to the falling number of sittings. As the government keeps restricting the Parliament's calendar, the Opposition's space to be effective is constrained. The NDA government has been uniquely tone-deaf to the concerns of the Opposition. The Opposition has been forced, therefore, to resort to disruption, as it is the only tool to bring this government to the discussion table.

State legislatures

As a Punjabi and Member of the Rajya Sabha from Punjab, I am concerned about the traditions and conventions of the Punjab Vidhan Sabha. Punjabi legislators should have pushed to increase the number of sittings. Instead, historical data shows that the average number of sittings has halved since 1966, when the state was reorganised into its current form.

Consider this: the last two sessions of the Punjab Vidhan Sabha, including one currently under way, will last a grand total of six days! In Kerala, on the other hand, the Vidhan Sabha sat for 151 days last year.

The Constitutional constraint for the state legislatures — Article 174(1) — also mandates a maximum of six months between sessions, giving the Governor, and by extension, the state Cabinet, the power to summon the legislature. The number of working days is, again, left to convention.

However, the Rules of Procedure of the Punjab Vidhan Sabha advise a minimum of 40 sittings each year — a guideline that has not been followed since the 70s, as the graph on the right shows.

Compared to Parliament, the state legislatures do not receive as much media attention or public scrutiny. While a few states, such as Punjab, Karnataka and Rajasthan, publish their debates and discussions on official websites, most states do not facilitate public access.

The states then, are as guilty as the Centre when it comes to shirking parliamentary responsibility and eroding the institution's credibility. The Indian federalism cannot perform to its fullest if state legislatures do not carry out their constitutional duties.

Constitutional amendment needed

As the data has shown, conventions in India do not hold over time. It was convention to appoint non-political persons to the post of Governor. It was convention to never disrupt parliamentary proceedings. It was convention to diligently deliberate on Private Members' Bills each Friday. The only solution to halt the steady decrease in the number of sitting days, therefore, is to introduce legislation by way of constitutional amendment.

The amendment must mandate a minimum number of working days for Parliament and state legislatures. This minimum number should include a certain proportion where the agenda is set by the Opposition, allowing for true accountability and democratic debate. Ideally, such a proposal should also mandate the creation of a set annual calendar, so that Parliament is not held hostage to the whims and fancies of the government.