238 steps to solitude in Shiva’s sanctum...

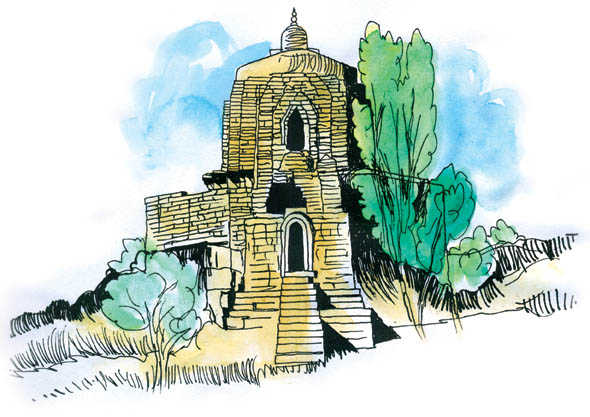

At the crack of dawn on Thursday, I found myself negotiating the steep steps to the Shiva Temple atop the Shankaracharya Hill in Srinagar. The 238 steps made a demanding climb. But what a glorious view of the city and its surroundings it was from the peak.

Though the temple’s history dates back to ancient days, it acquired an iconic name in the ninth century when Adi Shankaracharya made the place his abode for meditation and reflections on the revival of Hinduism. After achieving enlightenment here, the great sage “marketed” a new and progressive interpretation of the old religion.

It was a peaceful morning on the hill. Apart from the obligatory monotonous blaring of bhajans from a loudspeaker, there was nothing religious about the place. Instead, there was a profound spiritual calm. The city down was slowly stirring out of its slumber, and it was too early in the day for the hordes of tourists to crowd up the place with their meaningless cackle.

The magnificent Shiva lingam radiates the purest of feelings. Just a 15-minute meditation in the sanctum sanctorum at that hour of solitude felt wonderfully uplifting.

As per the archaeological folklore, the Lord Shiva Temple is sited at a place that was once known as “Takht-i-Sulaiman”. This “Sulaiman” was one of the commanders of some Hindu king in the region. It was disconcerting to see that the temple needed to be guarded by paramilitary forces. The CRPF camps stand out like a sore thumb.

However, I must confess that I have never heard any Kashmiri Muslim speak disrespectfully of the Shankaracharya Hill Temple, even during the darkest days of militancy in the state.

Like the Amarnath Temple, the Shankaracharya Hill Temple can only be understood as part of the body of attitudes and beliefs that was once called Kashmiriyat. Of course, the essence of that Kashmiriyat is no longer palatable to the hardliners on both sides of the divide in Jammu and Kashmir.

PAKISTAN's former foreign minister Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri is in India these days, primarily to promote his book, Neither a Hawk Nor a Dove — An Insider’s Account of Pakistan’s Foreign Policy. The dust-jacket markets the book as “an authoritative and revelatory account of secret Pakistan-India talks on Kashmir”. As could be expected, it is a Pakistani’s view of history and he is very much entitled to his interpretation of the cookie that crumbled. But, more importantly, Kasuri Sahib offers a rare but juicy and racy account of Pakistan’s political personalities and landscapes and the landmines.

Kasuri is a product of Panjab University, Cambridge and Oxford, and is an emblematic specimen of the pre-Partition elite in India. He is in Chandigarh today and is being made to feel very much at home. He interacts this afternoon with the city’s intelligentsia at the Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development (CRRID).

I AM not surprised that Ashok Vajpeyi has decided to join Ms Nayantara Sahgal in returning the Sahitya Akademi honour in protest against the rising tide of intolerance in the country, as exemplified by the lynching of a Muslim in Dadri village of Uttar Pradesh. He has never been afraid of speaking up — or, speaking out.

He is one of the most creative Hindi litterateurs in the country. When a majority of the English-speaking intellectuals were buying uncritically into the Narendra Modi spiel in the run-up to the 2014 Lok Sabha election, Vajpeyi remained gloriously unimpressed. He wrote the wonderful poem “Woh aa raha hai…” (“Awaiting a Felon”), a prophetic caution against the promise of the Promised Land being ladled out of the jumla-manufacturers.

However, what has been disappointing is the mixed reaction to Ms Sahgal and Vajpeyi’s act of intellectual courage. The two are being ridiculed as publicity seekers. Others are accusing them of being selective in their indignation. Why did they not feel so strongly in 1984, they question. Some are even, unbecomingly, asking: why not return the money?

More than the lynching of an innocent Muslim, it is this partisan skepticism that could be our undoing. We have entered the age of total cynicism and we shall trot out any argument — often a seemingly politically correct argument — only to disguise ugly prejudices.

IT may sound a bit too dramatic but let us recall that immortal poem, by Martin Neimoller, about what happened in Germany when people who should have spoken up refused to speak up:

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out — because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out — because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out — because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me — and there was no one left to speak for me.

Divisive politicians and their toxic rhetoric have played such funny games with our collective minds that we seem to have become afraid of our own good impulses.

I am reminded of a piece of wisdom from Zen Buddhism. The Korean Zen Master, Seung Sahn Haeng Won Sunim, says: “There is no right and no wrong; but right is right and wrong is wrong."

Every so often, each society’s burden becomes to discover — and, then, say it loudly — what is right is right and what is wrong is wrong. Nayantara Sahgal and Ashok Vajpeyi have helped us become aware of our obligation to make that discovery. We should be grateful to them.

THE invocation of the “Hoshiarpur days” in this space last week seemed to have kindled fond memories of very many alumni of Panjab University. A couple of readers were kind enough to point out that I had got two names wrong: It was Professor SB Rangnekar, and not Rangrekar, and, again, it was Dr GK Chadha, and not GS Chadha, as mentioned in the column. Errors acknowledged.

Perhaps the most interesting response came from (Major) Vijai Singh Mankotia, who says he was at Panjab University College, Hoshiarpur, when Dr Manmohan Singh began his teaching career.

As Mankotia puts it, the faculty was joyfully engaged in grooming the young minds and the entire university was a place for all-round growth.

Let him exaggerate a bit: “Historians, scientists, economists, mathematicians, the teaching faculty of that time comprised scholars who had few peers.

“The institution indeed contributed to the academic stream. At the same time, it also produced outstanding sportsmen. Theatre got prominence, the Tagore Literary Circle, the Talk Over-a-Cup-of-Tea (TKT), the Bazm-e-Abad that organised mushairas, the inter-college and inter-university debates. Hoshiarpur had created its own mini-Oxford or a mini-Cambridge of sorts, post-Partition.

“We were young, we were reckless and we were willing to take on the world. In the words of Omar Khayyam:

Ah! Love: could thou and I with fate

conspire,

To mend this sorry state of things entire,

Would we not shatter it to bits,

And mould it nearer to our heart’s desire.”

Those were the days. Indeed.

And, so, the question that should haunt us now is: how did we manage to squander away all that was so good and how have we become so enamoured of all that is second-rate and phony?

Coffee, what do you say?

kaffeeklatsch@tribuneindia.com