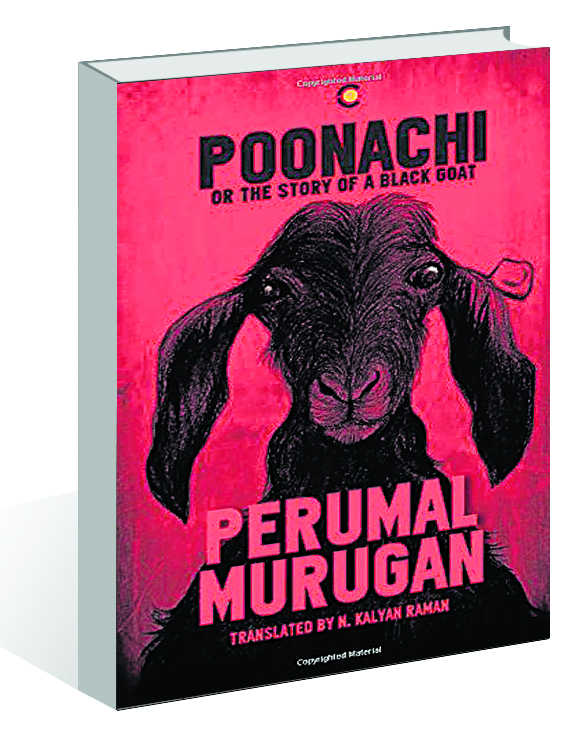

The goat song

Rumina Sethi

Perumal Murugan gained fame — notoriety rather — when he wrote Maadhorubaagan, or One Part Woman, about the esoteric rituals of the Gounders of Kongunadu, a community in Tamil Nadu, which practises free sex between women and unknown men on one day of the chariot festival.

Childless women, without fear or blame, can seek out other men under cover of darkness and get pregnant. Murugan’s story about this particular custom was so deeply censured by caste groups that he proclaimed himself ‘dead’ and wrote his own obituary. Even though the Madras High Court later declared that Murugan, being a writer, had no alternative but to write, it was not an easy journey thereafter. Words refused to flow.

Poonachi is one of Murugan’s post- Maadhorubaagan books. But in between the two, Murugan wrote another significant collection of short poems, significantly entitled Songs of a Coward. Here is an excerpt from one of his poems:

‘You took away everything from me

I now show you

A lap bereft of words

Please leave me.’

This short verse, and many more, bespeak of the writer (ironically of course) as a ‘coward’, who now produces in exile the kind of writing that should make most people happy.

Perhaps Poonachi, the eponymous pastoral story of a very tiny black goat is Murugan’s way of steering clear of controversy. As he says in the preface, he is fearful of writing about humans, and even more, about gods; or about cows and pigs because that is forbidden. But ‘goats are problem-free, harmless, and above all, energetic.’ There are human characters, too, in the story, but primarily to serve as side pieces. Though the story is in the third-person narrative, Poonachi speaks, wails, weeps and grieves like she were human.

A goatherd and his wife, both unnamed, receive the gift of this small goat, who is brought up on borrowed milk from the other goats kept by the couple. Eventually, despite the odds, she grows into a young ‘woman’ with physical desires and needs. No wonder she is kept away from other male goats reared by the old couple. But one day, when the old man and his wife visit their daughter, Poonachi falls in love with a young buck, Poovan. Thus begins the sad tale of love and despair, freedom and fright, desire and death, human and animal correlation and dissonance.

And though she has to leave heartbroken, fate beckons once again, when she spends a night of bliss with Poovan, where after, all of a sudden, Poovan is sacrificed to the gods. As Murugan writes: ‘We die for meat. We die for sacrifice.’ From here on, the novella becomes as black as the goat, and we detect layers of meaning camouflaged by animal characters. A devastating famine engulfs the entire area, and Poonachi’s kids, one by one, are butchered for meat.

Two questions are raised in this novella: Why does Murugan write about animals; and is it that he is afraid of writing about human characters. The background of the novel is bleak. The ‘regime’ hunts out ‘criminal’ dark goats, tags them with identity chips, surveils and interrogates from birth to butchery. But the powerless are also sometimes able to subvert the system. Murugan may be quiet, yet he says what he has to say subversively. Murugan may well have turned to animal stories to avoid being judged in terms of caste, religion, patriarchy or sexuality.

Ultimately, it is the system that wins despite occasional rebellion and escape into freedom. Poverty, hunger and control exercised by the state hegemonically does violence to dignified human endeavour, and cannot be resisted. Ordinary and docile lives, such as Poonachi’s have ‘mouths only to keep shut, hands only to make obeisance, knees only to bend and kneel, backs only to bend, and bodies only to shrink before the authorities.’ As Murugan has written autobiographically:

‘I have commanded my pen

That the ink-drip from its ball-tip

Shall happen henceforth

Only for signatures

accounts and

journal entries.’