How Delhi developed its New part

Pankaj K Deo

Nothing can describe better the phoenix-like resilience of Delhi as the capital of India than this oft-quoted couplet of Allama Iqbal: “Yunan-o-Misr-o-Roma sab Mit Gaye Jahan Se Ab Tak Magar, Hai Baki Naam-o-Nishan Hamara, Kuchh Baat Hai Ke Hasti Mit-ti Nahin Hamari”. Delhi became a forlorn city in the 19th century, especially after the Indian uprising of 1857. The last Mughal emperor was exiled and the city lost its status as the capital of India.

The British ruled the Indian subcontinent for all practical purposes from Calcutta, a city that the East India Company had created and developed for both trading and administrative purposes. Calcutta, as the new administrative capital, prospered as the epicentre of all political, social and cultural developments under the colonial rule in the 19th century.

As a corollary of the European education that the British ushered in, a class of educated Bengalis vehemently opposed to the British rule emerged in Calcutta. Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy, could sense this initial stirring of a nationalist movement against the British rule. He decided to break the back of this movement through the partition of Bengal in 1905 on communal lines, which was later revoked due to the massive outrage it caused. The British grew apprehensive of this restive population of Bengal and decided to embark on a new strategy that involved political reforms through devolution of power and the transfer of the capital.

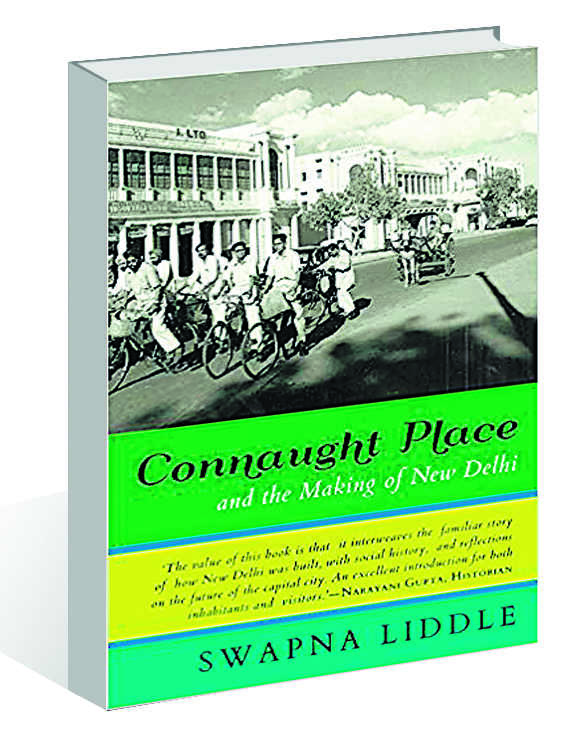

Swapna Liddle’s book, Connaught Place and the Making of New Delhi, traces the development of New Delhi as the capital of Imperial India, which lies sandwiched between two partitions: the Partition of Bengal in 1905 and the Partition of India in 1947. The book traces the history of New Delhi from the announcement of the transfer of the capital at the Coronation Durbar held on December 12, 1911 to the city’s evolution in the post-independence era.

Once the decision to set up a new capital was announced by George V at the Durbar, the entire colonial administration set out to complete the task with the steadfastness the British are known for. Liddle’s book tells you how the architect duo — Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker—collaborated to translate Lord Hardinge’s idea of striking a balance between Western architecture with Indian decorative arts into reality. Unlike the preceding rulers, the British created a city that sought to accommodate the democratic aspirations of the subjects, no matter how superficially.

Unknowingly, they created a city that could serve as the capital of a democratic republic that India became after Independence. Most buildings could be repurposed to the needs a new nation. Thus, Legislative Assembly became the Parliament; the Viceroy’s House was turned into the Rashtrapati Bhavan. The Secretariat Building still houses the top echelons of Indian bureaucracy. That the British had an inclusive outlook on India’s history is evident from the way they named the roads after India’s emperors—from Ashoka to Aurangzeb.

To cater to the needs of the occupants of the new city, a shopping centre, Connaught Place, named after Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, was set up, which drew inspiration from Park Crescent in London. This shopping mall was one of its kind with tailoring shops, salons and cinema halls such as Plaza Odeon, Rivoli and Regal. Most of these theatres have now turned into multiplexes.

Like Rome, New Delhi, too, was not built in a day, and the book traces the tribulation of the town planners and offers new insights into the minds of the policy makers who conceived it as the capital of an empire where the sun never used to set. The book tells us how the concept of garden city was incorporated into the plan, and how the bungalows of New Delhi seem far more inclusive than the gated apartment complexes of the NCR.

The newly born city was bursting at seams when it had to provide shelter to the large influx of refugees in the wake of India’s Independence and Partition in 1947. However, the new gentry, mostly from Lahore, more than made up for the exit of the British from the scene; they infused a new spirit in the city, and New Delhi gained from what Lahore lost forever.

The book is a treasure trove of information on New Delhi and a must-read for all who love this city.