Faces of war

Lt-Gen Baljit Singh (retd)

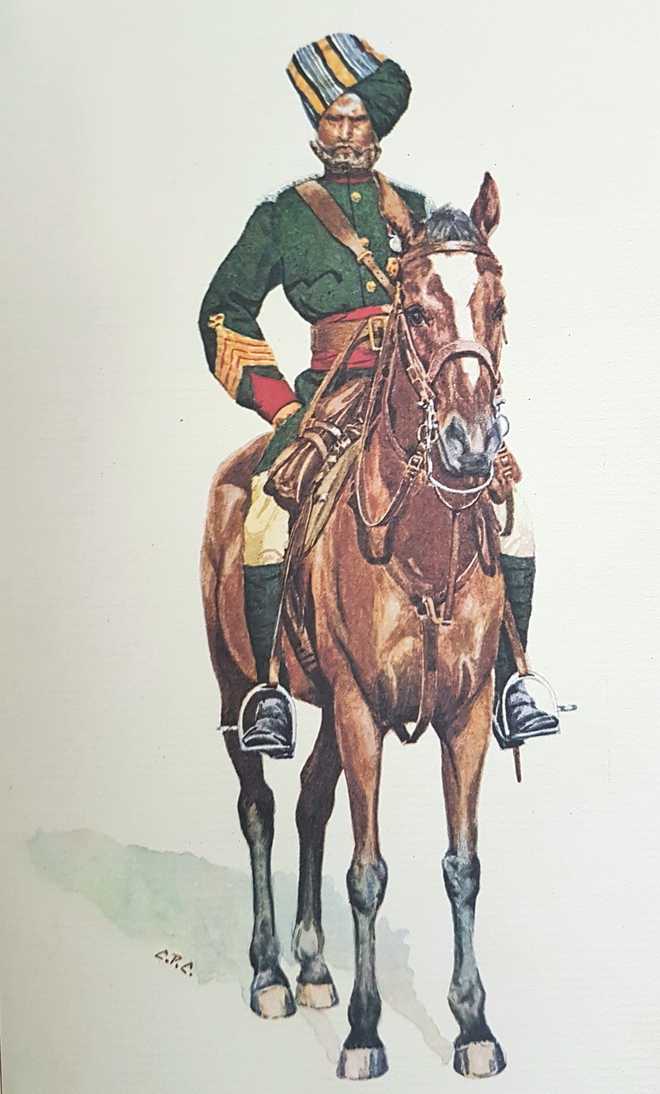

An expert on historical Indian Army uniforms had once opined that it was “a tragedy that the artists who got the uniforms right always painted the wearers as if they were stuffed dummies, while those who could paint real live men always fell down on the details of the uniform”. As a generalisation, this is depressingly true but happily there is one exception from my reading experience; the enigmatic CPC, born to British parents in Calcutta in 1897, who post baptism emerged with the singularly unusual name, Chater Paul Chater.

After a childhood of plenty and fond indulgences, when sent to England to study mining engineering, he did not, as may be imagined, pursue it to conclusion. Fortunately for CPC, his uncle Sir Paul Chater, one of the great Hong Kong merchants, used him as an office aide assigned to gain social links than any secretarial advantage per se. In the process, CPC travelled widely in the East Asia and married Aileen Balthazar, daughter of another great Eastern Trading House of the 20th century!

When the war broke out in 1914, CPC first enrolled with the Shanghai Volunteer Defence Force, but evacuated to Britain shortly after and was commissioned in the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), with whom he served till the armistice in France and Gallipoli, as a Captain. After the war, he settled in London but both he and his wife were deeply attached to the Far East and found the English winters unreasonably cold. But they had the means and spent most of their days on the Riviera, ultimately hiring lodgings of a more permanent nature at Nice. That is when he set up an atelier to paint pictures of Indian Army uniforms.

He had had no academic or prescribed training in art and his extraordinary skill with paints and brush was the most surprising since, on the surface, he was a hearty, charming, outdoors type, always easy-going and exuberant. He had a plus handicap at golf and was a confirmed pub goer. In England, he was a habitué of The Pembroke Arms in the Earls Court Road, where he founded a private drinking circle known as The Mice; a comedian’s popular assertion that he “was paid on Friday night and spent Saturday morning chasing Pink mice with a butterfly net”!

However glorious and accurate the uniforms he depicted, yet the portraits of the wearers per se were always fascinating. Yet, it is improbable that he ever painted from a live model as Indians of the military classes were almost unprocurable in Earls Court at that time. He, therefore, based his pictures entirely on printed material mostly from magazines such as the Illustrated London News and the Navy and Army Illustrated, both periodicals with a very high standard of photographic reproduction. None of them, of course, was printed in colour. Indeed, colour printing in those days was as likely to mislead as to inform. But CPC went to great length to obtain precise details of colour and design as stipulated in “The Indian Dress Regulations” and similar reference books, of which he acquired a fine library. He was also a regular student at the India Office Library, checking details that he could not confirm elsewhere.

According to his son-in-law, he would start by making a rough sketch, paying particular attention to the face in order to ensure that it was correct for the particular regiment — Sikh, Dogra, Pathan, Punjabi or whatever it might be. His next move was to check all the details of colours, badges, medal ribbons against the Dress Regulations. Having got all the uniform details in note form on his rough sketch, the next step was to do the head on a much larger scale than the figure was to be; this was to ensure that all the detail was correct before reducing it to fit on the body in the final drawing. All the colour details and fine work on the eventual drawing had to be painted under a magnifying glass. A few of the preliminary drawings of heads, some in more than one version, have been preserved and are reproduced in several books.

Not all the source material was in the form of photographs. Some creations of CPC were indeed from live models from such Indian soldiers who were on duty at Buckingham Palace or among those who appeared for any Investiture Ceremony. Occasionally, a pose was adopted from an earlier painting but every detail was cross-checked and verified. Above all the face was a genuine creation of CPC and the figure had none of the woodenness of so much of similar work.

CPC was generous to a fault and if a visitor was attracted to a portrait, CPC would gladly gift the piece without ado! Shortly before his demise, the atelier was burgled of close to a hundred art works. CPC ceased to paint and lost the zest for living.