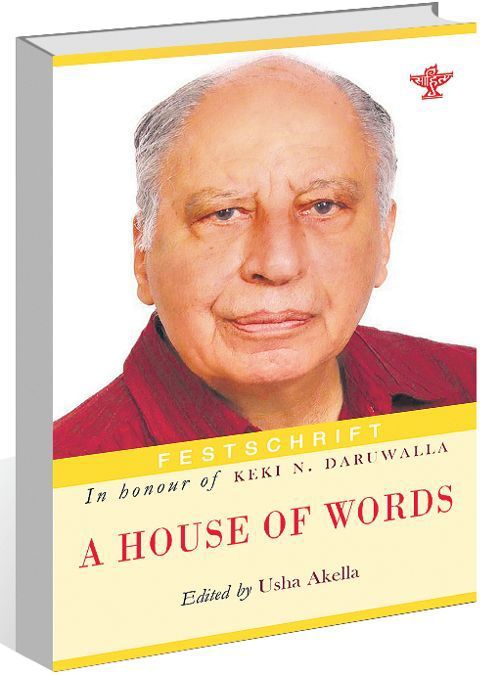

‘A House of Words’, a festschrift for Keki N Daruwalla: Fusing memory and scholarship

Sonya J Nair

BORROWED from German, festschrift roughly translates into celebration writing. In my mind, it is the written form of a group of people raising a toast to a person of consequence on an important occasion like retirement or birthday. There is a tendency in India to celebrate lives after they have passed on, to make elaborate eulogies and to ponder on the significance of their contributions to the future. That is why the festschrift celebrating Keki N Daruwalla is a beautiful idea. And it is probably providential that the idea of this festschrift did indeed occur as a spin-off of Keki’s 85th birthday. In her introduction to the book, poet, critic and academician Basudhara Roy describes the sequence of events whereby poets and admirers got together on a virtual platform to celebrate Keki’s birthday. Two people simultaneously came up with the idea of a rather unique gift and then, Usha Akella, the redoubtable editor and one of the two dreamers, carried the idea over the finishing line.

This festschrift is not just a vanilla narrative of what Keki Daruwalla has written or how he is placed in the annals of Indian poetry in English. Rather, it is also a very comprehensive process of historicising Indian poetry from an inside-out perspective. When poets themselves seek to chronicle history, it makes for a very interesting and insightful read.

In the course of reading, the book throws up many nuggets of knowledge and commentaries of the state of literary chronicling in India. The lack of recognition for some of the country’s greatest modern poets is galling. There is also, at the same time, a short-sightedness in terms of acknowledging and contextualising the contributions of these poets in shaping the vocabulary of imagination of Indian poetry in English, which is something that this festschrift seeks to lead the way in correcting.

‘A House of Words: Festschrift. In Honour of Keki N Daruwalla’, published by the Sahitya Akademi and edited by Akella, is a solid work that fuses memory and scholarship with beauty and legacy. One gets the impression of walking through a museum — where the first section reflects on some of the signature work of the poet. Then, in the next section, the poet is fondly remembered by his friends and mentees, of whom there seem to be many. Travelling through the festschrift, one understands that Keki’s generosity with his time and his words have directly shaped many poetic careers. The narratives, interspersed with anecdotes, are warm but not, thankfully, saccharine. They bring out the kindness of Keki that lies underneath his seemingly gruff exterior. I suppose being a policeman could do that to you.

The last section contains two interviews on his craft, which make for very entertaining reading.

In an interview with Akella, when asked about his ability to write on diverse cultures across historical periods, he cheerfully ascribes it to longevity spent in the company of books. The interviews contain his voice and one can hear him in his ‘house of words’: “…father was a professor, had remained in England from 1914 to 1921 or 22. There were 3,000 books at home. When he retired, he got swindled of his Provident Fund by a broker. What are Professors for if not to be swindled by crooks? God made both in his large scheme of the cosmos. The Divine also anticipated the lot of Indian politicians and Vice Chancellors, many of them caught plagiarising. I also refer to the VCs, the politicians who don’t know even how to plagiarise. I am told they are putting up a school in Amdavad to educate them in this subtle art!”

In one fell swoop, he makes the personal and the political merge into a statement that readers would have to keep coming back to. The book goes on to reveal the perceptions of creativity and of creative writers that Keki has formed over time. The next sections are some of the most intensive studies of any poet’s works that I, as an academic and a critic of poetry, am yet to see.

Akella has compiled and commented on some of the most compelling imagery and aphorisms in Keki Daruwalla’s works. His aphorisms, or ‘Kekisms’ — as she terms them — are delightful and bring out the impish impulse the man has. An example:

“This myth of roots is overplayed. There is nothing great in being stuck in the same hell-hole.”

‘A House of Words’ has reminiscences from some of the best-known names in Indian poetry in English — from Adil Jussawalla, Saleem Peeradina (who passed away before this book could be published), Arundhathi Subramaniam to Menka Shivdasani to Yezad Kapadia to Sukrita Paul Kumar, Pramila Venkateshwaran, Priya Sarukkai Chabria, Namita Gokhale, Rukmini Bhaya Nair, Thomas AJ, Malashri Lal, Sanjukta Dasgupta, Sridala Swami, Harish Trivedi and many others. These and other luminaries speak of the ways they have seen the poet at work — of how he has dealt with crushing losses, how he views vital issues such as menstruation, the capacious memory he has, his popularity and above all, his towering personality.

‘A House of Words’ is an apt festschrift. It is a gathering of intelligent people raising a glass in honour of a man who has built a house of words, in a world of words and who still seems to have so much to say. It is a compelling work of enduring significance.

I hope it leads by example to inspire more such thoughtful festschrifts or memoriams. Here’s to Keki Nasserwanjee Daruwalla!