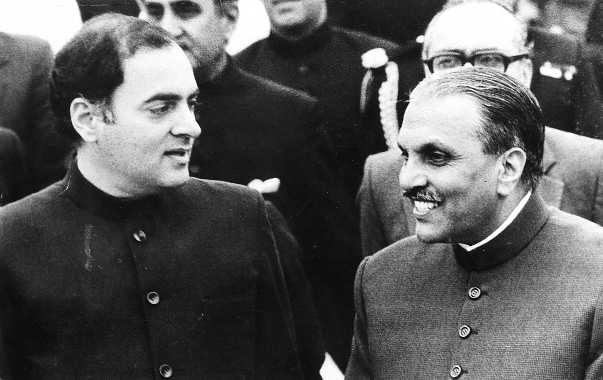

Enemies forever: During an unannounced visit in 1987, Zia-ul-Haq warned Rajeev Gandhi of a nuclear attack in case of an Indo-Pak war

Sandeep Dikshit

Sometimes a treasure trove lies in plain sight while people walk around it. This is exactly what happened about the shadow games played over Afghanistan between 1984 and 1988. The implosion that took place after the US walked away with its part of the cake still reverberates in a wide swath of region, including India. Over the years, leaders of developing countries around the world have paid the ultimate price for crossed wires with superpowers: Patrice Lumumba, Salvadore Allende, Mohammad Daud, Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, Hafizullah Amin.

Ambassador John Gunther Dean, one of the extraordinary ones who have graced American chanceries, also adds Zia ul-Haq to the list. His allegation, soon after Zia died in a ball of fire, triggered a chain of events that were also extraordinary like the man himself: Dean was declared mentally deranged and recalled to the US. The world never ever paid heed to his version of the diplomatic and political conditions in those years that kicked off the age of terror.

Dean took over the Indian assignment after two extremely tough tenures in Cambodia and Thailand, which saw him featuring on the Newsweek cover. In order to signal a change in the US attitude towards India, then under a new PM in Rajiv Gandhi, Ronald Reagan selected Dean, as he sent the right vibes with four previous ambassadorial assignments. The book is a product of several containers of Dean’s personal papers with Ronen Sen, another prominent personality of that era, by the author’s elbow. The papers had never been declassified and Dean, now 90 and still sprightly, helped the process by persuading the CIA to release them.

What unfolds is a remarkable story of an attempt to set right the imperfections in the region left behind by a new version of the Great Game in the 1970s and the 1980s. Ronald Reagan detected the possibility of Rajiv Gandhi serving as a backchannel conduit between the US and the Soviets at the funeral of one of the geriatric stop-gap Soviet Presidents between the handover from Brezhnev to Gorbachev. Interspersed in the book are vignettes of a world seldom revealed: the modus operandi of envoys to strike proximity with world leaders, that the Indian intelligence was comfortably plugged into the Pakistani army’s communication grid; the backhand deals at multi-lateral settings and the double dealing that the Pakistanis handed out to the Soviets.

As the intrigue and confabulations for a peaceful Soviet withdrawal followed by a neutral government gather pace, events race with each other and collide, setting off sparks that lead to death and destruction. Diplomats shed their equanimity, leaders soaring on the high of confabulating with the great and the mighty crash land rudely.

This book gives another perspective to the narrative about Afghanistan that is dominated by Arabs and Pakistan. India, as the biggest power in South Asia, had a firm hook in Afghanistan. But it all came apart by 1988 when the US decided to let Pakistan beg and steal nuclear weapons technology because it felt India had been adequately used for getting the Soviets out of Afghanistan. In another decade, Pakistan achieved strategic parity with India by testing a nuclear weapon in 1998.

As a diplomat, Dean saw and chronicled everything; and he believes the so-called US war on terror was avoidable if sincere attempts had been made to form a broad-based government after the Soviet withdrawal. Had all the participants maintained their initial sincerity, who knows, Karachi might have been hosting beauty shows today and Kabul a city of intersection of cultures of South Asia, Persia and Arabia? Kallol Bhattacharya keeps his nose close to the ground during the four years of an attempt to repair the region, narrated crucially from the Indian standpoint, which is usually air brushed in commentaries emanating from the West and Pakistan on the events of 1984-88.