The great divide: The narratives in these books recount painful memories without the tinge of animosity or polarised perceptions

Kuldip Singh Dhir

Partition remains a gaping hole in the heart of Indian subcontinent. Discourse on Partition has changed radically over the past 70 years. Historians and litterateurs are revisiting it without being trapped by curse of mutual animosity, distrust or polarised perception. They reject binaries and borders in spite of the atmosphere of hatred and bigotry in the country. It was a rewarding experience to see this bottom-line in this eminently readable set of books on 1947 which make a complimentary read. Bishwanth Ghosh gazes at the borders and the people around these. Narendra Luther gives us a heart-wrenching personal account of the harrowing experience of leaving empty-handed his ancestral home with danger and death all around. Rakshanda Jalil, Tarun K Saint and Debjani Sengupta present a miscellany of essays, memoirs and different literary genres from across the borders leaving us ponder over the lessons of history.

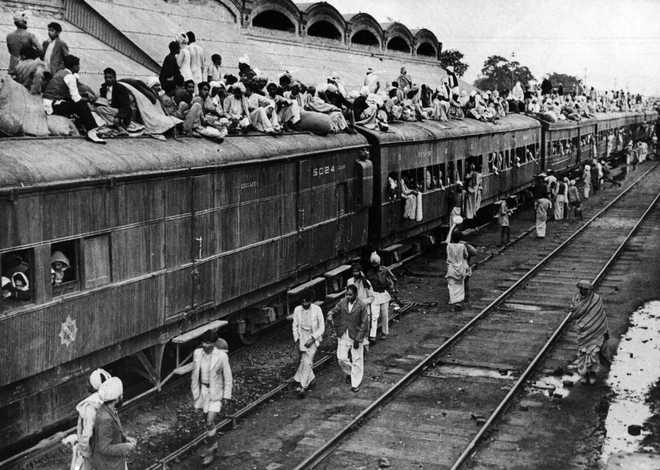

Ghosh has chosen to gaze along and across the dividing lines drawn by Cyril Radcliffe. He took merely five weeks to draw a line 553 km long in the West and 4,096 km long in the East of India. Incidentally, new countries were created without demarcating boundaries because Radcliffe Award was made public on August 18. Uncertainty about demarcation added to the mayhem making one million lose their lives, 10 to 15 million leave their homes and one million women abducted. Ghosh visits Attari, Wagha, Hussaini Wala, Dera Baba Nanak and border villages to give us a firsthand impression of past and present of Partition in Punjab. We listen to Bir Bahadur Singh recalling the times when his father beheaded all women members of the family to save their honour form frenzied mobs. Yet, he believes that common man wants peace. He points out that prior to introduction of passport and visa system in 1952, Punjabis would freely walk across the border. Indo-Pak wars hardened the attitudes for some time after which anger and animosity gave way to nostalgia.

Bengal saw less bloodshed in 1947. It was the transfer of population there that was a staggered process. The borders are soft and porous. There are houses where border line runs through the courtyard. There are places where a road divides two countries and the shortcut offered by it is allowed as a harmless concession to the citizens. People exchange pleasantries and often visit each other across Agrtala, Boxanagar, Karimganj and so many other places. In fact, culture is their true identity and nationality a mere technicality. Flag-lowering ceremony on the eastern border is devoid of jingoism associated with Wagha.

Narender Luther is maternal grandson of renowned Punjabi poet Kirpa Sagar. He was living in Rawalpindi since 1946. As a high school student he was a witness to Muslim league agitation of March 1947 which led to wide spread rioting making Hindus and Sikhs flee to India. Narendra’s mother gave birth to a son on July 21 and in early August they left the Muslim-dominated area in Rawalpindi to shift to an area with concentrated non-Muslim population. They heard Nehru’s Independence speech there. His father, who had opted to stay in Pakistan, was asked by his Muslim boss to shift to his son’s house disguised as Muslims. They shifted but the prospect of improvement in the situation looked bleak. They decided to leave for India after staying with the Muslim family for over a month.

Luthers boarded a special train from Lahore on October 18, with beds, daily clothes and some eatables. All compartments and roof of the train were occupied with innumerable people and their language. The train was guarded by Gurkha soldiers wielding guns. The slow moving train stopped at various places for extended intervals. Sounds of sloganeering, sights of arson and exchange of fire continued all along its way. The train completed the 50-km distance from Lahore to Amritsar in three days and two nights after surviving five attacks on it. Nine dead bodies were recovered from it when they reached Amritsar.

The anthology edited by Jalil, Saint and Sengupta is neither region specific nor genre specific. It assembles diverse genres from Punjab, West Pakistan and East Pakistan, which is now Bangladesh, restoring a sense of plurality and responsibility to reactions to the events. Zakkia’s Sadae Baazgasht describes a situation where riot victims don’t have a new country to migrate to. Doosra Kinara by Ashraf examines the ‘communal othering’ which is accepted unquestioningly by the young today. Amena’s Allah-Ho-Akbar underlines disillusionment faced by Muhajirs. Anwar Ali’s novel Gwachian Gallan gives in new insight that for those at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid, Partition meant nothing more than a willing change of religion. Excerpts from Fikr Tonsvi’s dairy speak with passionate intensity of the bloodshed faced by Punjab. Mirchandani recreates and relives days of Partition through her memories. The interview between dying Nasir Kazmi and Intizar Hussain cherishes memories of what they left behind. Sahir and Javed Akhtar’s poems speak about the disillusionment that followed independence. Art historian Salima Hashmi dwells on the idea of a home which can be a safe heaven or be a under siege when times change. Asghar Wajahat’s Jis ne Lahore Nahin Dekhya gives us a glimpse of dilemmas faced by those who decide to migrate and those who refused to do so. Saibal Gupta gives a peep into the Dandakarnkia, India’s largest refugee rehabilitation programme. There are memoirs, short stories and poems from Bangla literature which provide an ironic look at the distortions that 1947 wrought on our psyche and remind us about what partition failed to divide.

Taken together these three books enable us to enter the interstices of 1947 that are liberating and sombre, giving a more nuanced understanding of the vivisection and its afterlife. These make a plea for shifting our focus from annihilating violence to redemptive kindness and wish that governments open up channels of communication and people’s interaction. We must all aim for a continuity into the present of a shared past. Exclusivists might frown at such ambitions but majority of people on either side of the border share this incessant innocent desire.