|

Colours of folk art

Tribal and folk art forms are among the most glorious living traditions of India.

Charu Smita Gupta chronicles the evolution and resurgence of these in her book

Indian Folk and Tribal Paintings. Excerpts:

ART,

among the tribal and folk communities in India, was never indulged in

purely for pleasure. Its purpose was equally to pacify the malevolent

deities and to pay homage and express gratitude to the benevolent

ones. Festivals are linked to the two agricultural crop cycles of

sowing, reaping, harvesting, and storing; festivities are also related

to events such as birth, puberty, and marriage.

Kolam, a custom in

south India entailing daily decoration of the mud floor, was

considered essential to welcome the household deities. In the belief

that paintings on walls and floors bring peace and harmony to the

dwelling, the main doorway of the house, the inner quarters, the

kitchen — all display painted details for protection of the

household goddess and to ward off evil. Apart from colour, clay

relief-work is also used for similar purposes.

The Agaria and Gond

communities of Madhya Pradesh, Harijans of Madhubani and many groups

in north India, particularly girls in Haryana, work with clay. These

clay relief decorations, known as sanjhi, may be termed as painted

appliqu`E9s, with lumps of clay, either plain or mixed with rice husk

and jute, and are customarily used as material for creating forms.

Today, when one

speaks of tribal and folk paintings in India, one has to look at the

vertical as well as the horizontal spectrum. Historically, paintings

created on rock surfaces by wandering communities were undoubtedly the

first recorded expression of art. Art forms of the settled communities

also appeared on the walls and floors of their dwellings. Vertically

speaking, the art of painting expanded from floors and walls to other

surfaces like clay, terracotta, stone, wood, ivory, glass, leather,

palm-leaf, fabric, paper, papier-m`E2ch`E9 and coconut, using one, two

and three dimensional surfaces. Horizontally, regional and

community-based diversification of the styles of painting became

distinct. Paintings led to the development of temple murals and

fragments of these depictions appeared on wooden storytellers’

boxes. Slowly, with technological advancements, the new materials

became the additional surfaces on which to paint.

|

Madhubani

Madhubani is the

heartland of Mithila, the ancient country of the Maithilas,

located in the Madhubani district of Bihar. Madhubani is derived

from the words madhu and ban, meaning the ‘forest

of honey’, which implies the land of prosperity. Madhubani

paintings were also recognised as ‘Kulin’ art or the art of

the pure castes. Women from all strata of society — the

Brahmin, Kshatriya or Harijan — practised Madhubani folk art.

Traditionally, the paintings were executed on the walls of three

places in the home — the gosai ghar (room of the family

deity), the kohbar ghar (the room for newly-wed couples),

and the veranda outside the kohbar ghar used as a sitting

room for visitors. Kohbar paintings symbolise fertility and

creation. |

|

Thanjavur Paintings

The Thanjavur painters traditionally belong to the Telugu-speaking Raju community, who are Kshatriyas in the caste hierarchy. The composition of Thanjavur paintings is static and the centrally placed deity commands the space, with a minimum of narrative or illustrative detail. The main characteristics of Thanjavur paintings are the gilding and the gem-set technique. Gold leaf and precious and semiprecious stones are luxuriously fixed to depict the jewels and dresses worn by the icons. The child Krishna is an important icon in these paintings. |

|

Bhil Paintings

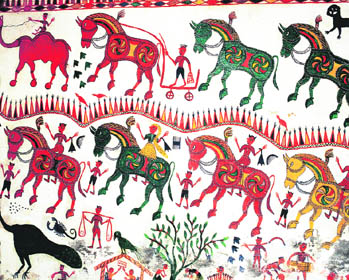

The Bhils and Bhilalas of Dhar and Jhabua in Madhya Pradesh and the Rathwas of Panchmahal and Baroda districts of Gujarat display characteristic ritual wall paintings created by traditional caste groups known as the Lakhindra.

These paintings depict the story of creation, and the myth thus depicted, centres around the tribal god Baba and his nephew, Pithoro. Members of the Lakhindra caste group are chosen to execute these ritualistic. The main character of the Pithoro painting is the horse. Often, iron moulds of the horse in different sizes are used to draw the outline. The main characters of Pithoro and Pithori are painted in white on cow dung-plastered walls. Pithoro paintings among the Rathwas of Panchmahal and Baroda districts of Gujarat are luxuriously colourful and ornamental. |

|

Warli Paintings

The name ‘Warli painting’ has emerged from the tribe called Warlis, who live in Thane district of Maharashtra. The traditional drawings in Warli paintings are the chowks. Palaghat, the most significant mother goddess, is shown seated in the chowk. Palaghat, the deity, is drawn by making two triangles, with their tips meeting each other in the centre. Since Warli tribals are agriculturists, Hariali Deva, the god of plants, also occupies a prominent place in the Warli pictograph. Other characters in the traditional Warli painting are

Pancha Sirya Deva, the five-headed god, and the headless warrior, who is either standing or riding a horse. The selective imaginative use of triangles, circles and dots, only in white, on a muddy surface, gives a perfect magical vibrancy to the paintings done by the Warlis. Rice paste was the traditional medium used for the drawings on mud walls. |

Excerpted with

permission from Indian Folk And Tribal Paintings by Charu Smita

Gupta. Roli.

|